The Center for Global Initiatives (CGI) at the Johns Hopkins School of Nursing provides students with the opportunity to travel to different countries to address complex global health challenges. Students visiting Nepal work and learn in a multidisciplinary and interprofessional environment that incorporates expertise from physicians, non-physician providers, nurses, and public health experts at an international site. Read on for the experiences students had during their time abroad.

Olivia McHugh

Before I went to Nepal through the Global Health Leadership Program, I considered myself a pretty experienced traveler. I’ve been to over 20 different countries across 5 continents, and in each place, I did my best to learn about its people, culture, and values. But I had never been abroad in the context of healthcare. My time in Nepal helped me to realize that studying a country’s healthcare system is a powerful way to learn about cultural norms and values.

In Dharan, a city in Nepal’s Terai region, my colleagues and I had the opportunity to shadow students, nurses, and doctors in the different wards at B.P. Koirala Institute of Health Sciences. We saw how Nepali nursing students are educated – with extensive clinical time and an emphasis on the use of practical skills, rather than machines, to provide care – as well as how nurses and physicians work together in fast-paced, resource-strained settings like the emergency department. I witnessed open-heart surgery in an operating theater in 100-degree heat – a standing fan helped to cool the surgeons as long as the power stayed on (it went out three times, leaving the room in sweltering darkness). I visited a community health clinic providing free antihypertensives, birth control, antibiotics, and diabetes medications. I watched in awe as a nursing student several years my junior single-handedly delivered a baby. Over and over again, I was shown that healthcare workers are resilient and creative in overcoming obstacles.

Perhaps most importantly, I saw the ways in which global health partnerships can strengthen both Nepali and American healthcare. A lack of resources – in terms of medical devices and equipment, medications, and access to current research – hinders Nepali healthcare. However, the people of Nepal are benefitted by an emphasis on prevention and a substantial amount of government resources dedicated to providing primary care and essential medications. Public health workers explained to us that children receive all of their vaccinations for free, and that trained paramedics make regular in-home visits to all residents older than 65.

In comparison, American healthcare focuses on treatment of acute illness rather than disease prevention. This reactive focus leads to poor health outcomes and greater strain on our healthcare infrastructure. When I asked healthcare workers in Nepal about the success of preventive medicine there, they responded that the Nepali people believe in taking care of one another. Some attributed this to religion, others to tradition or social values. Whatever the reason, their approach to public health could strengthen the American healthcare system.

I was extraordinarily lucky to get to learn about foreign healthcare in such an immersive way. The vast majority of people, however, will never have the opportunity to spend a month in the lush hills of Dharan. That is why supporting global health partnerships is of critical importance – not just to countries with limited financial resources, but also to wealthier countries seeking solutions for outdated healthcare systems. Knowledge exchange and collaboration, after all, are pillars of excellent healthcare.

Aliza Lurie

My time in Dharan, Nepal was chaotic, complex, joyful, exhilarating, enduring, and captivating. Many of these emotions seemed to happen simultaneously at any given moment, while others were prompted over extended patient or interprofessional discussions, both outside and inside the clinical setting.

Needless to say, both my internal and external environment was consistently buzzing, charged with energy, racing thoughts, and endless curiosity. Traveling presented challenges as it always does, and lessons to be learned about control, independence, culture, and self. I challenged myself daily with staying present in my mind and body and witnessing the experience at hand as fully as a possible.

Being dropped in a foreign country with a foreign culture and language is shocking at baseline, and for days I was exhausted by the sensory overload of the whole experience. When I reflect on my experiences in the inpatient and outpatient clinical settings one of the most striking memories I have is of the sense of universality of health-related conditions, specifically in the mental health space.

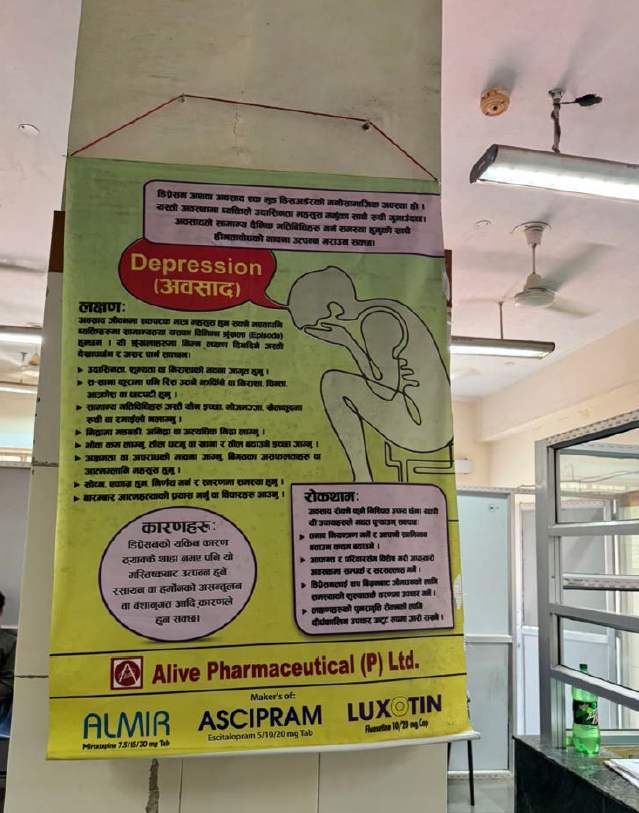

Objectively this concept of universality and “sameness” seemed obvious, but I couldn’t help but sit in awe and contemplation as I witnessed how similarly anxiety and panic disorders, depression disorders, psychosis, and trauma related stressor disorders persisted and were experienced by Nepali people. Worlds that seemed so far removed from one another, and resourced in vastly different ways, struggled with the same health concerns.

I reflected on the impact of mental health outcomes that the lower resourced setting in Nepal would absorb, and the endless morally challenging decisions that were made based on financial means, medication allocation issues, and practicality concerns. All of which was usually at the cost of the patient’s health.

The sameness of the effects on social, cultural, and emotional sectors of life related to mental health disorders on the Nepali patients created a sense of closeness and familiarity of this struggle. In this resemblance, I found comfort and was reminded of all the universal methods of therapeutic communication and management that I had learned and utilized in my practice in the States. I practiced and witnessed other clinicians extend themselves empathetically towards patients in crisis, in struggle and dysregulation, and as I had seen in my clinical settings at home, the therapeutic connection blossomed between provider and patient, creating an authentic, trusting, and effective clinical relationship.

Throughout my trip to Nepal I could feel the space between my familiar home and where I spent three weeks of my semester break. Initially the distance felt exotic and risky but as I woke up each day and let it unfold, the familiarities of life experiences reminded me that in our humanity there is much more that is shared than different.