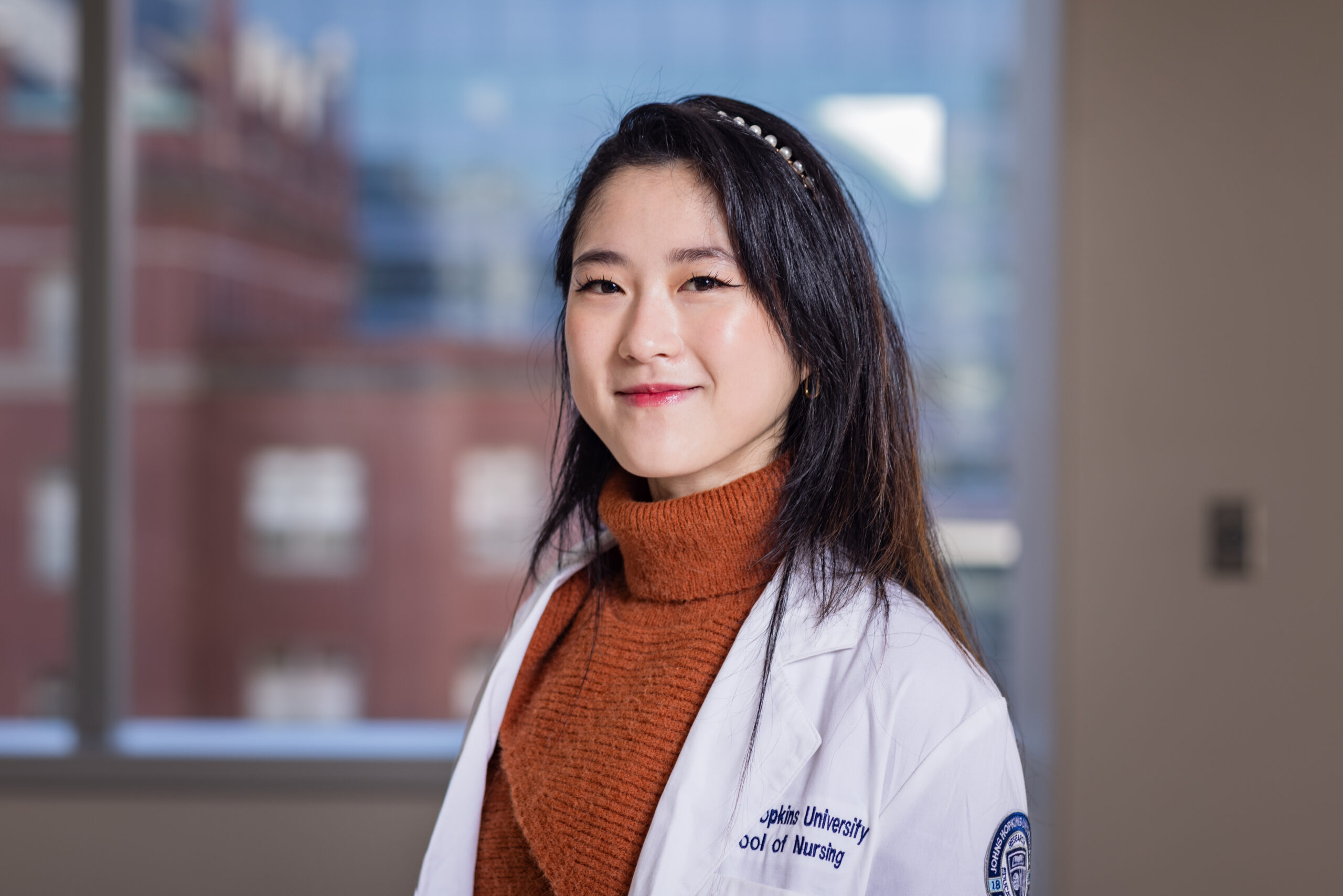

Having been there, DNP psych student Euna Yang hopes to nudge ‘lost’ young people toward healthier perspectives on food.

Having suffered the physical and psychological effects of bullying and bulimia for more than

a decade—from being labeled “the fat kid” on her native Guam, through undergraduate studies at Carleton College in Minnesota, through dieting culture, unsuccessful eating-disorder programs, and endless family and group therapy sessions—Euna Yang was an empty shell.

“There was this one moment,” she explains. “I was inpatient for a while, and I left for about a week, and I was already slipping and sliding. I was hovering over the toilet, and I had just purged everything that I had eaten, and I was contemplating how much pain, how much suffering this felt like. ‘I’m kind of not really living right now, and I hate this and hate everything that has been happening.’ I had quite lost my way.”

She credits the care and nurturing of a nurse practitioner at the Melrose Center in Minnesota with rescuing her and inspiring within Yang a mission to help others stop the ache, a key part of why she joined the Doctor of Nursing Practice (Psychiatric Mental Health NP) program at Johns Hopkins.

“She took the time to actually get to know me, to kind of show me, ‘Hey, this is an option for you. I think this will be good,’ and to teach me about the medications,” as opposed to a parade of psychologists “who barely looked up from the clipboards or computer screens to talk to me. I had medications that I had no idea what they were—I still don’t know what I was on.”

A dietitian and a strength coach continued the rebuilding process. “They helped me reconfigure the way that I saw food as something that is nourishing and helpful, not the enemy. That I can engage with it without feeling a loss of control,” she says.

Today, three and a half years into a recovery that she openly compares to an alcoholic’s sobriety—“You know, I have bad days, and it’s still like background music”—Yang is studying remotely for her DNP while working as an adult psych nurse at a small clinic in the Pacific Northwest. She earned her master’s in nursing from the Johns Hopkins School of Nursing in 2023 and serves as a teaching assistant at the school as well as volunteering with the Birth Companions and as a student group leader with the Chicago Parent Program, listening, empathizing, and sharing positive parenting skills “to hopefully break the cycle.”

“Covering all my bases,” Yang explains of a route that she hopes ultimately will end in pediatrics and early interventions to blunt the patterns that can lead to eating disorders. The path might one day also lead back to Guam. “The island’s quite small. You can drive around it at 35 mph in about three hours. It’s a very tightknit community and there’s not a lot of resources.” Back in the day, she says, the idea of a psychologist working with eating disorders was only that, an idea. The isolation was devastating. “I didn’t even know who to ask for help.” That has improved, she says, but there’s always room for another person to care.

“There’s this delicate balance of being the force that drives progress and also being able to give that space for people who just kind of need to take it all in.”

Wherever Yang ends up, there will soon be one more preceptor as well. Frustrated by the shortage—everywhere—of seasoned mentors in nursing, particularly in psych, Yang is determined to help fix that as soon as she’s got enough NP experience to begin sharing.

Meanwhile, she works to embrace the good parts of her own childhood. Though ultimately brutal on her psyche, Yang’s youth was filled with beautiful sounds that still move her. As a member of the Guam Territorial Band, she toured globally, including a competition at the glorious Sydney Opera House

in Australia, where the Guam kids earned the gold and—as Yang remembers—rock star treatment as children from competing orchestras chased the winners’ bus down the street cheering and waving goodbye. “It was so cute!”

Yang’s instrument is, or now mostly was, the flute, “a saving grace as well as one of the prisons I was in. It saved me in that, because I was part of the band, I was able to meet a whole host of amazing people who even to this day I talk with. At the same time, the flute was initially forced upon me. But I grew to love it. It’s quite nostalgic for me now and I really appreciate the chance that I got to do it.”

Though performing is no longer a part of her life, Yang finds peace and, often, tears of joy in the music she once made. She singles out the “Studio Ghibli Medley,” a collection of the works of composer Joe Hisaishi that add even more emotion and delight to beloved Hayao Miyazaki animated films like Howl’s Moving Castle, Spirited Away, and Princess Mononoke.

“I always cry whenever I hear it.” (If you happen to have the score at home, please flip to the section labeled “One Summer’s Day,” and grab a tissue along with her.)

The movies themselves “taught me how to love, about friendship, and about the different facets of humanity … and also gave me great role models of powerful women who looked like me.”

Hers is a perspective on life and survival that Yang will work passionately to pass on, especially to young people facing demons she has known by name.

“There’s this delicate balance of being the force that drives progress and also being able to give that space for people who just kind of need to take it all in. [Care for eating disorders] is a lot to adjust to. And I think the way of dealing with it is to let the individual be the guiding force. Obviously, treatment won’t work until they themselves want it to work. That’s the case with me. They threw all sorts of family therapy and group therapy at me, and it didn’t really click until I wanted it to.” ◼