Jason Farley, PhD, MPH, ANP-BC, FAAN, FAANP, AACRN, is an Infectious Disease Epidemiologist and a board-certified primary care Adult Nurse Practitioner with more than two decades of clinical practice experience. He is the Associate Dean of Community Programs and Initiatives and Directs the Center for Infectious Disease and Nursing Innovation at the Johns Hopkins School of Nursing. His research, clinical practice, and center activities strive to optimize a patient’s movement along the infectious disease care cascade. His team has extensive experience in initial diagnosis, health system navigation, and strategies to enhance retention in care. As a health systems scientist he designs multi-component behavioral and health system interventions that seek to build an equitable care experience adaptable to the individual’s need.

What drew you to working with Tuberculosis patients?

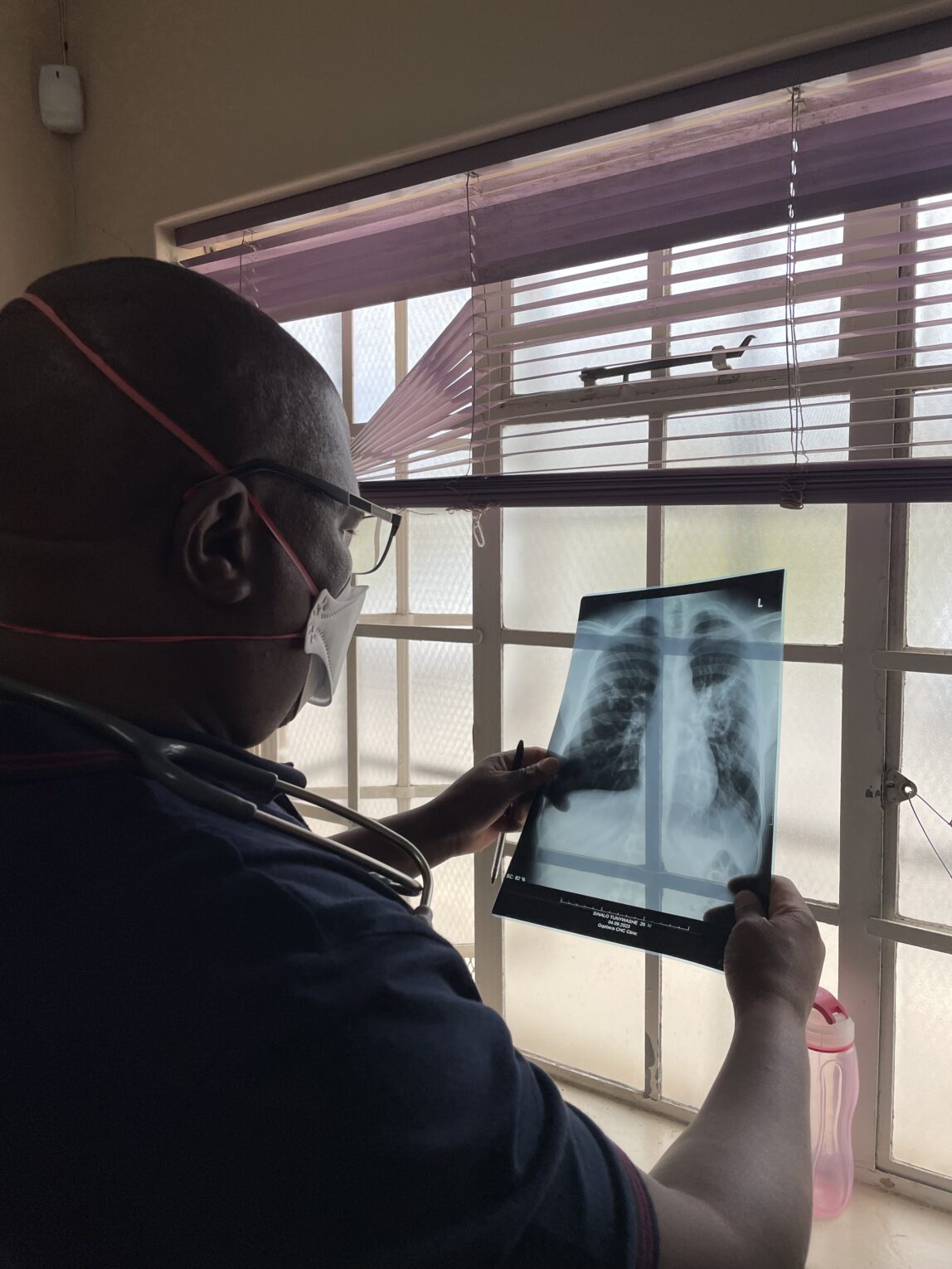

Tuberculosis (TB) is the leading cause of death in people living with HIV and the leading cause of death globally from an infectious disease. TB is a disease of poverty, malnutrition, substance use, and any condition that compromises overall immune status, like diabetes. TB is a curable infection, yet antibiotic resistance threatens treatment outcomes around the world, and I am particularly interested in persons who have antibiotic resistant forms of TB infection. Resistant TB is not only more difficult to cure, antibiotics for this treatment are also potentially more toxic. Finally, physician-based care models are structured in specialized facilities far from where people live or their primary care clinic.

What drew you to working in South Africa?

South Africa is a unique setting in which TB and HIV co-infection is highly prevalent. Additionally, drug-resistant forms of tuberculosis are quite common. In the early 2000s I started working in South Africa as part of a large cohort study investigating treatment outcomes for drug-resistant tuberculosis patients. In this study death was common. Almost immediately I saw so many opportunities to improve the structure of the health system to optimize treatment outcomes. My collaborators and I began brainstorming opportunities that we could address and thus launched two decades of research dedicated to saving lives.

Where has your research made the biggest impact?

I think my team has contributed significantly to understanding the epidemiology of antibiotic-resistant TB in South Africa. As a nurse epidemiologist work is informed by thoughtful inclusion of the health system processes, structures, and behaviors that reduce patient access, engagement, and retention.

In a cluster randomized trial evaluating nurse case management to improve the treatment experience for patients with drug resistant TB, we discovered that such an approach can reduce treatment failure by 45%. This is an amazing finding and means that patients demonstrated greater treatment adherence, despite profound side effects to the treatment.

We also were the first to demonstrate that linkage to care for new diagnosis of antibiotic-resistant TB was possible in less than 4 days. This showcased the potential for laboratory integration of diagnostic results with app-based linkage to care by community healthcare workers was not only feasible, but it was also paradigm shifting.

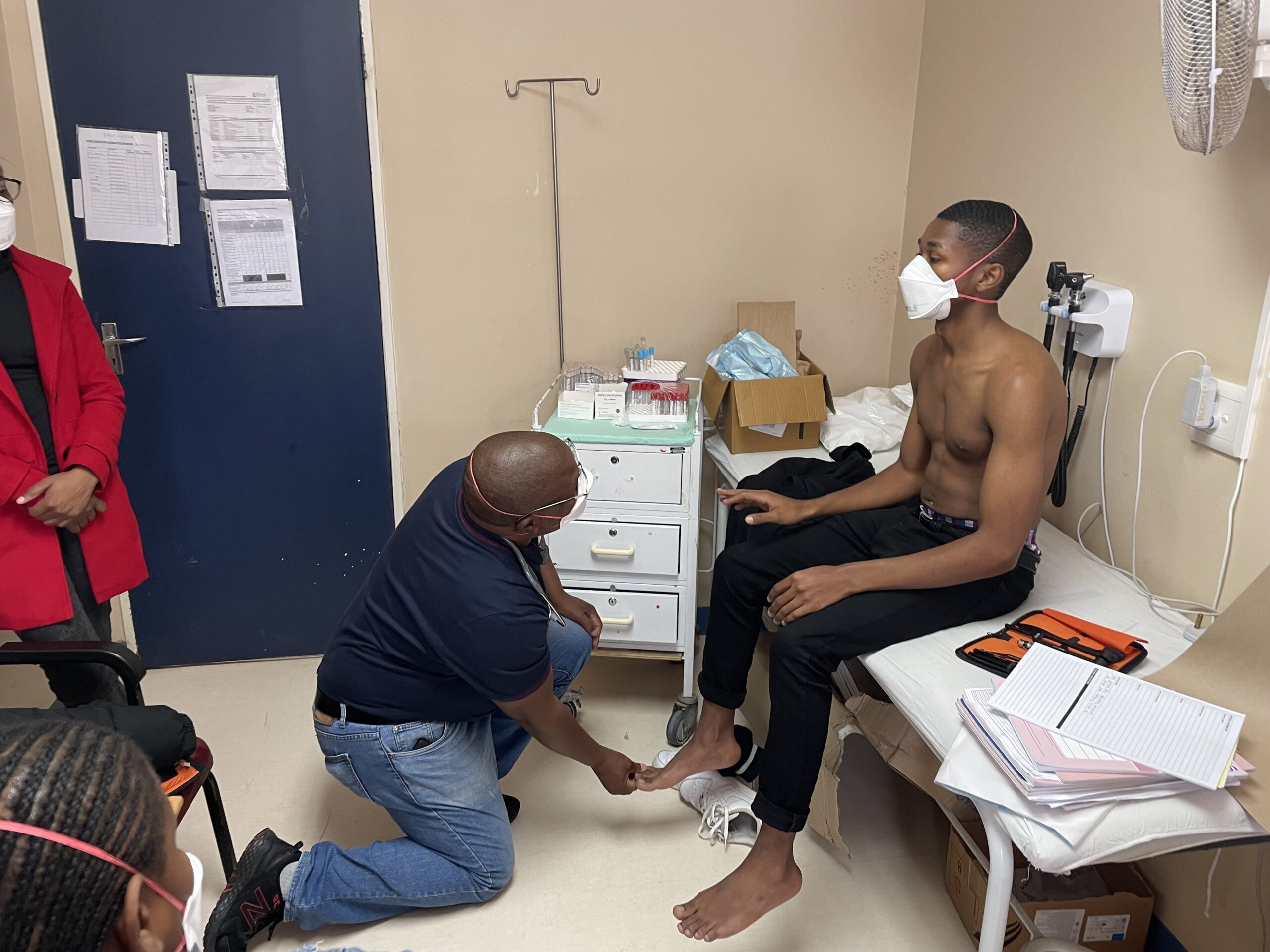

Detailing the impact of social and structural drivers on loss to follow-up from treatment, (i.e., travel distance, costs associated with treatment, or food insecurity) is another key area of our work. This led us to begin looking for alternative models that would bring care closer to the patient’s home. We implemented a clinical training program in which nurses were trained to diagnose treat and manage patients with drug resistant tuberculosis. We worked with the National Department of Health to put this model into practice and conducted a retrospective cohort study to evaluate treatment outcomes. We found that treatment outcomes in this observational study we’re equivalent in the nurse and the doctor arms. We also found that no patient felt the care they received from the nurse was inferior to that of the medical officer. This finding changed national policy guidelines in South Africa in 2013. Nurses were recognized in those guidelines to be an acceptable alternative to physician-based treatment.

Given that high level policy impact over a decade ago, are nurse’s now the primary driver of drug-resistant TB treatment in South Africa?

Despite national guidelines allowing nurses to treat drug resistant TB patients, the uptake of this intervention has been slow and uneven throughout the country. One of the major reasons for the slow uptake is that the recommendation was based solely on observational evidence. The gold standard for adoption of system level change is most often the randomized controlled trial. Yet no clinical trial to date has evaluated nurses compared to physicians for the management of drug-resistant tuberculosis. As such each province in South Africa implemented nurse-led treatment in an individualized way. From 2013, our team collected additional programmatic evidence that we used to support an application to the National Institutes of Health in support of the necessary clinical trial evidence required for more broad adoption of the nurse-led model.

Where does the research stand now?

In 2023 our team was funded to conduct a cluster randomized non-inferiority trial evaluating nurse-led drug-resistant TB treatment in comparison to a physician-led standard of care model. We have included more than 200 primary care clinics across 76 clusters and have a robust safety and cost effectiveness evaluation as well. Our preliminary data on outcomes and safety look promising. Through this primary care model, we are bringing care within walking distance for many patients. Sadly, this research, like many other NIH funded efforts is under threat. We are facing a bleak season with many uncertainties. Yet, my team is hard at work contemplating how to save our science and to ensure this work carries forward.