Thirty armed Salvadoran gang members surrounded the car, stopping it so that it couldn’t go forward or backward. Inside, Meghan López—who’d brought along college student volunteers, several of them young women—realized she’d miscalculated. They’d rolled into a gang-controlled territory, windows up, unidentified and unannounced.

“It was one of the few times I was genuinely scared,” explains López, whose work with children and families in vulnerable situations has stretched from Paraguay (with the Peace Corps) to Peru, El Salvador, Guatemala, and pretty much all of Latin America. “OK, get ready,” she told her volunteers, who were terrified, “either we get out, or they’re opening the doors.” Her instructions: Be pleasant and calm. Greet every person (in this case every gang member). Shake his hand. Look him in the eye. Say, “Good afternoon! I’m here to work with the children!” And follow her.

Meanwhile, López also shook hands, locked eyes, said “Good afternoon! I’m so happy to see you! My name is Meghan, and we work with children!” in fluent Spanish and herded her charges toward the nearby children’s center, where she apologized to the wide-eyed workers, offered another date for a return visit, apologized again, and calmly led the group back to the car, bidding farewell to the gang members (clearly thrown off by the charm offensive) in the same manner. “So nice to meet you! We’ll be back that date. Bye!” Shaking hands. It wasn’t until they’d driven 10 miles down the road that, still shaking themselves, López and her troupe stopped the car and … had a moment.

Disaster averted and protocol established, the group would become regular visitors, watched—perhaps videotaped, maybe having their phones checked—but welcomed within this territory and others. Because deep down, in a nation where at least half of all gang members have fathered children, these were mostly just parents concerned about their kids having good health and a better life (despite exerting control over their territory). Sessions featured activities for both children and parents, recognizing that children’s health and well-being also required looking at parent’s health and well-being. Though these were gangs with histories of brutal violence themselves—in a nation where 75% of gang members are recruited by age 12, 90% by age 18—they were, more importantly, communities who wanted things to be better for their children.

And in such communities is where López has found her calling, by listening and learning about priorities, hopes, and peoples’ own ideas for how to fix things. It started in Paraguay, where her Peace Corps posting featured 27 homes. López stayed at each for a couple of days, sharing meals, listening, learning priorities, and over two-plus months earning trust. Basic needs were water, for which villagers relied upon the local river and mountaintop springs, and medical care, a two-hour walk and a dodgy, unreliable bus ride away. “I was meant to be a beekeeping and soil conservation support for the community. That was what they originally asked for. And instead I ended up doing a lot of WASH—water, sanitation, and hygiene activities—and family gardens, and nutrition” (as she also worked with a local NGO to get health workers established in the community).

It was another lesson that has stayed with López, who returned to the United States to earn a BSN at the Johns Hopkins School of Nursing in 2007, an MSN there in 2011 (while working at Johns Hopkins Hospital), and then her DNP in 2019—earned after she’d relocated to Nicaragua and then El Salvador to work with the child protection organization Whole Child International. “It was a mix of child health and child protection, and from there really grew their programming to also looking at communities and families and public policies and structures.” While moving the needle on children’s well-being, it was “at that point I realized that a lot of the problems we were running into with child protection and child health and well-being was really due to violence, and not just violence but transgenerational experiences of violence and how that impacts people’s health, mental and physical, everything.”

(Her DNP project involved breaking cycles of transgenerational violence by improving child outcomes through parenting interventions.) From there, López joined the International Rescue Committee, working in El Salvador and advancing to regional vice president for Latin America.

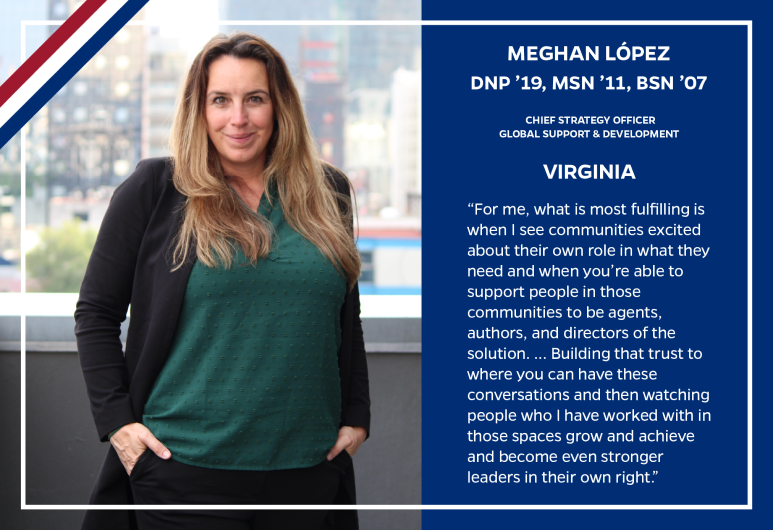

Today, López serves as chief strategy officer at Global Support & Development. López has also served as an NGO representative to the United Nations in New York and earned Johns Hopkins University’s Global Achievement Award and the Johns Hopkins Innovation in Health Research Award for her doctoral work.

Photo Credit: Patrick Tombolo

Meghan López in El Salvador

“For me, what is most fulfilling is when I see communities excited about their own role in what they need and when you’re able to support people in those communities to be agents, authors, and directors of the solution. … Building that trust to where you can have these conversations and then watching people who I have worked with in those spaces grow and achieve and become even stronger leaders in their own right.” — Steve St. Angelo

Click here to learn more about the programs at the Johns Hopkins School of Nursing.

Go to unitedstatesofnursing.org to see more stories in The United States of Nursing.