Nurse practitioner Ellie Tsikalas admits she carries the job around with her sometimes. In her decade at BrightStarts Pediatrics in Alabama, she has witnessed a great deal of need—and hurt—among her young patients and their parents in a community diverse in racial and economic makeup but not in mental health specialists.

“Huntsville, like so much of our nation, suffers from a lack of mental health care options,” explains Tsikalas, MSN, BSN ’03, CRNP. “When I started in pediatrics, it was next to impossible to find a psychiatrist to see one of my suicidal teenagers, let alone something ‘simpler’ like mild to moderate anxiety. There was also a long list of kids at my clinic wanting ADHD testing but not finding a specialist to get it done.”

So, “Sometimes, you just have to do it yourself,” Tsikalas says of her choice to become one of those experts in assessing and treating ADHD. “BrightStarts is a very high-volume clinic, treating newborns to strep throat to whatever. The physicians didn’t have time.” And the closest specialists were at Vanderbilt in Tennessee or the University of Alabama-Birmingham, each a two-hour drive.

The desperate need was right in her face. The tools? Tsikalas wasn’t sure what was available, but she knew what she was after. “It was finding tools that were proven for ADHD assessment,” she says. “What works for me? What works for the clinic? And what do I trust?” Then there was educating parents (“What does this assessment mean?”) and working with schools on medications, therapy, and children’s other needs.

Having been there, Tsikalas now seeks opportunities to share what she’s learned and encourage/prod those who might be leaning toward helping but unsure of how to proceed. “My first conference talk, for a meeting of NPs from the state of Alabama, was called ADHD for the Reluctant Primary Care Provider.”

Subtle.

“Sometimes you don’t have a choice,” she says of becoming a specialist where none is available. “Someone has to step up and figure it out.”

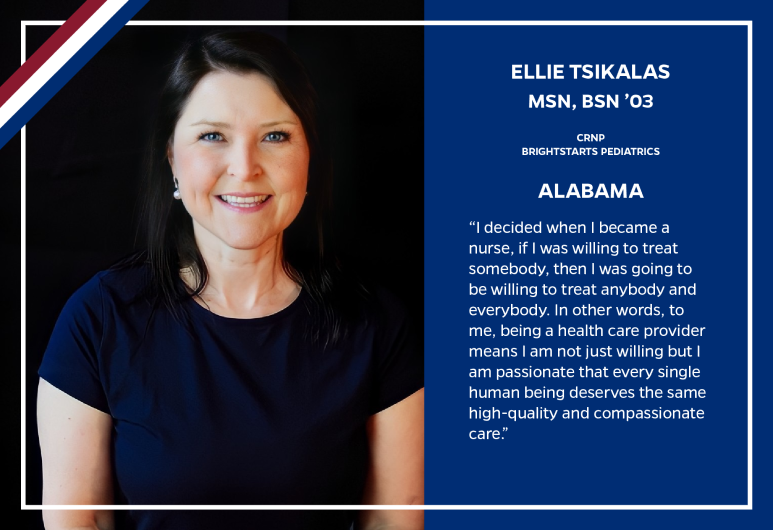

“I decided when I became a nurse, if I was willing to treat somebody, then I was going to be willing to treat anybody and everybody. In other words, to me, being a health care provider means I am not just willing but I am passionate that every single human being deserves the same high-quality and compassionate care.”

It can be stressful, but she insists it is beyond fulfilling.

Luckily, Tsikalas has an outlet or two. Family is a husband who works for the Missile Defense Agency after a Navy career flying C-130 mega-cargo planes to war zones and other overseas destinations. (Flying makes Ellie a wreck; “blood and medical stuff” make Manny’s knees week. Perfect couple.) And son Simon, now 16, reintroduced Mom to a love of community theater. She’s been Mrs. Beauregarde in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory and spent several months on stage as a nun in The Sound of Music opposite Simon, who played Friedrich von Trapp.

Ellie Tsikalas has seen a lot in her life and career, from a Pennsylvania youth growing up exposed to art—falling in love with the music of Les Miserables after a visit to Broadway at age 8—to the Bayview burn and trauma unit in Baltimore to cardiac telemetry on the Pebble Beach golf course in California (“where patients were allowed a glass of wine with dinner so long as their medical team signed off on it”), to Pensacola, FL, to Corpus Christi, TX, to Willow Grove, PA, to Hunstville.

But seeing Simon across the stage—Ellie Tsikalas admits she was genuinely awed by the moment. “Even if it never happens again, I got to live in a magic world.”

Simon is currently performing as Seymour in a local production of Little Shop of Horrors. Ellie is between roles, theatrically anyway.

For the lessons of the stage are never very far away: “Actors have a saying, ‘You need to deliver the lines just as clearly and deliberately at your final performance as you did at your first performance.’ You the actor have repeated those words a million times. But there are people in the audience on that last night who have never heard the words before. … I remind myself of this, and also teach it to my nursing students or preceptees: When you diagnose your seventh strep throat infection of the day, and you have given the same exact instructions to six other families in six other rooms, the mom and child in that seventh room deserve the exact same explanation and education.”

(Applause.)

— Steve St. Angelo