Nurse-midwives use frontier technology to bring quality care to women where they are

In Dziwe Health Center in Blantyre, Malawi, nurse-midwife Precious Dausi is using a portable ultrasound scanning device during women’s antenatal visits to determine accurate gestational age and identify potential complications early. A continent away, in India’s Gogunda community health center in northwestern Rajasthan, nurse-midwife Sumitra Kumari Bhamawat uses a tablet-based app in the labor room to retrieve women’s comprehensive antenatal history and keep a close watch on the progress of their labor, receiving alerts in case of any complications.

Never before has frontier technology reached so close to where women live, providing nurse-midwives like Dausi and Bhamawat working in remote, often understaffed and overburdened health facilities, with the tools to offer better and timely care in the rural communities they serve. “In the past, nurse-midwives at our facility could only offer basic antenatal care, such as checking heartbeat, monitoring growth and, in advanced stages, checking the position of the unborn child. They could not make exact findings by palpation of a woman’s abdomen,” says Dausi, 28.

Thinking around digital health in nursing and midwifery for any setting should not be restricted by a lack of consistent electricity or other poor infrastructure.”

The World Health Organization recommends that pregnant women receive at least one ultrasound scan before 24 weeks’ gestation. But in Malawi, a country that has adopted the WHO guideline at the national level, this service is unavailable in many rural health facilities like Dziwe. In rural areas, only pregnant women who have been identified with a potential complication that requires ultrasound confirmation are referred to the tertiary referral hospital for scanning, which could be miles away. This process can lead to ill health and even death as complications are often identified at an advanced stage of pregnancy.

To address this situation, Jhpiego, a global health leader and Johns Hopkins University affiliate, with funding from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF), started implementing a research study within the ANC/PNC Research Collective (ARC) to assess the feasibility and acceptability of integrating an ultrasound scanning device, Butterfly iQ, with antenatal care. Testing different strategies to introduce obstetric ultrasound services is a priority for the Malawi Ministry of Health as it works to improve the quality of antenatal care.

The Butterfly iQ is a rechargeable, handheld digital scanner that can help overcome barriers of inconsistent electricity and lack of computers at most rural health facilities. Users download the Butterfly iQ app and connect the scanner to a phone or tablet, which displays the images. Being portable, nurses are able to provide ultrasound at the point of care, even in the remotest areas. In partnership with the Malawi College of Medicine-Johns Hopkins University Research Project, Jhpiego is training 50 rural nurse-midwives like Dausi with the knowledge and skill to use the Butterfly iQ to expand access to ultrasound and reach 1,500 pregnant women.

Digital tools can be a force multiplier in the hands of health providers in low- and middle-income countries whether they are assisting in infant circumcisions, learning new diagnostic skills, or helping map underserved communities that need HIV prevention and treatment. Jhpiego is investing in digital health strategies to accelerate delivery of quality of care where it counts.

“Thinking around digital health in nursing and midwifery for any setting should not be restricted by a lack of consistent electricity or other poor infrastructure. Many patient and provider technologies are being developed with use of a smartphone which can be solar-powered and we know the global south has outpaced the west in everyday digital functionality—such as SMS mobile money and cash transfers,” said Pandora Hardtman, Jhpiego’s chief nursing and midwifery officer. “In several of our programs across diverse geographies, we are working to capacitate nurse-midwives to use technology, not only to provide quality care, but also to break barriers to equitable access to health information and services.”

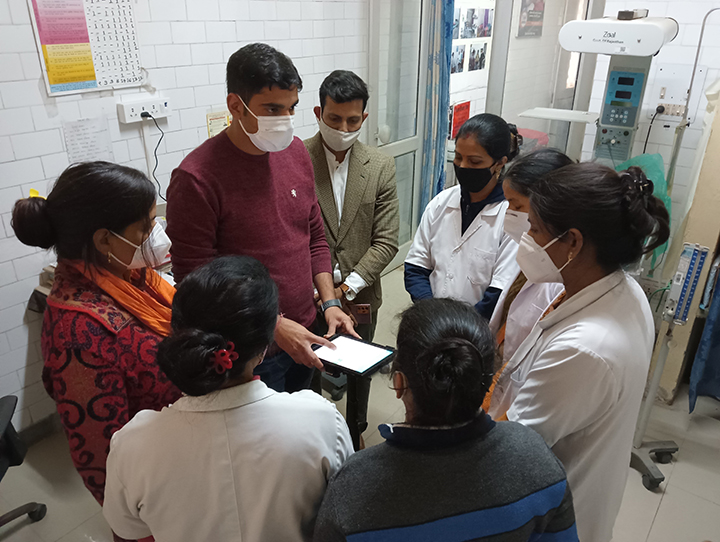

In Rajasthan, India, for example, under the BMGF-supported, Jhpiego-led Antenatal Risk Stratification—Intelligent Continuum of Care program, nurse-midwife Bhamawat and her colleagues have learned to use a tablet-based app called Prasav Watch (meaning “delivery watch”). The app flashes a red alert in case of complications and prompts the health worker to take timely action. “We are catching life-threatening conditions in time,” says Bhamawat. “The app has also reduced the need for referrals,” adding, “the referral site gets a similar alert and receives all [the woman’s records] through the app before she arrives.”

In addition, digitized antenatal care (ANC) records are now available to labor room staff

like Bhamawat through a 16-digit unique ID number that the mother received during her

ANC check-ups.

The uses of people-centered, provider-oriented technology are vast, says Hardtman.

“From patient wearables to health information, data analytics to capacity building via Artificial Intelligence and Virtual Reality, nursing and midwifery has to adapt and embrace digital technical or be left aside as irrelevant to our changed world.”