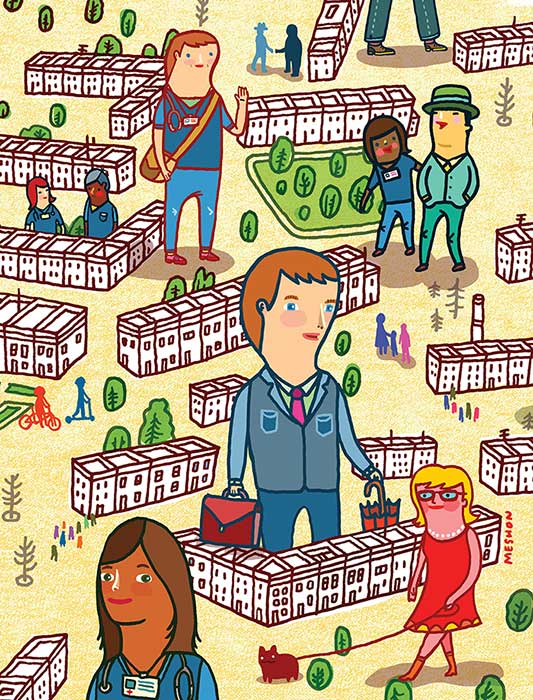

In East Baltimore, Hopkins Nurses can go to great lengths to help and learn without straying far from campus

By Elizabeth Heubeck

It’s a little after 9 a.m. on a Friday morning, and Teresa Pfaff, BSN, RN, a public health nurse, is just settling into her office, tucked down a hallway on the first floor of Apostolic Towers, a subsidized housing facility for low-income adults in East Baltimore within walking distance of the Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing. No sooner does she throw up her window for some fresh air and turn on her computer than her first client of the day wanders in the open door and sits down in a hard-backed chair against the wall, waiting to be seen and heard.

Pfaff greets the elderly gentleman by name, pulls her desk chair close to him while retrieving a folder on the client, and leans in. “So, what’s going on?” she asks, meeting his gaze. It’s not the first time they’ve met. Last time he was in, Pfaff checked his blood pressure and they talked about ways to reduce his pack-a-day smoking habit. Today, the gentleman is concerned about a significant reduction in his monthly Social Security check. “Let’s see if there are other Medicare Savings Programs to apply for,” she says reassuringly. A knock on the door interrupts the meeting. An emergency visit needs to be scheduled: One of the tenants is about to be evicted.

Pfaff greets the elderly gentleman by name, pulls her desk chair close to him while retrieving a folder on the client, and leans in. “So, what’s going on?” she asks, meeting his gaze. It’s not the first time they’ve met. Last time he was in, Pfaff checked his blood pressure and they talked about ways to reduce his pack-a-day smoking habit. Today, the gentleman is concerned about a significant reduction in his monthly Social Security check. “Let’s see if there are other Medicare Savings Programs to apply for,” she says reassuringly. A knock on the door interrupts the meeting. An emergency visit needs to be scheduled: One of the tenants is about to be evicted.

This tiny office serves as the headquarters for the Isaiah Wellness Center, one of three School of Nursing (JHUSON) faculty directed, service-learning program sites in East Baltimore. In addition to its walk-in, nurse-run wellness center that provides an array of preventive and education services in the office or in residents’ apartments, Isaiah also draws from JHUSON undergraduate and graduate students seeking experience in community health nursing to develop targeted, on-site health education programs for residents. It’s a win-win arrangement, as community members gain access to convenient and reliable preventive health resources and, in turn, nursing students develop skills in providing community health nursing and learn to identify root causes of health disparities among low-income minorities in ways that could never be taught in a textbook.

Pfaff and others who are studying to become advanced practice nurses partner with Hopkins medical residents to make home visits in Apostolic Towers. It’s a service of the Isaiah Wellness Center and, more broadly, an initiative developed and championed by Rosalyn Stewart, MD, associate professor of Medicine at Johns Hopkins. It’s based on the premise that interprofessional education helps achieve the best health outcomes through effective collaboration among students from different disciplines, offering an opportunity to reconsider the traditional model of health care delivery.

Pfaff, in the MSN/MPH program at Hopkins, describes an instance in which she and a medical resident provided an intervention for a resident of Apostolic Towers who had temporarily disappeared after being diagnosed with cancer. “They wanted to get him in [to surgery] quickly for a radical procedure. We tracked down the patient and had a personal half-hour conversation with him about the procedure,” Pfaff recounts.

The patient agreed to the surgery, which went well. Pfaff believes the interprofessional intervention played a pivotal role in the outcome. “We were able to ‘tag team’ and work collaboratively, playing off of each other’s strengths,” she says. “That balance and interplay allowed us to deliver a very patient-centered intervention at just the right time.”

What’s good for the patients is also good for the students. “It certainly has been beneficial for the learners. They have a better appreciation of the skill set each can bring to the table,” Stewart says.

Steps From Campus

Nurses naturally want to make things better–and they don’t have to be in a hospital to act on that instinct. Many, it turns out, actually prefer to practice outside the hospital. The East Baltimore communities that surround the JHUSON campus happen to be the perfect living classroom for first-year undergraduate nursing students to veteran nursing professors and researchers.

Consider Perkins/Middle East, a Baltimore City neighborhood of approximately 7,300 residents within a stone’s throw of Johns Hopkins. In 2000, according to the Baltimore City Health Department, 41 percent of its adults between the ages of 16 and 64 were unemployed. Seventy percent of the community’s households earned less than $25,000 annually. The Johns Hopkins nursing community recognizes that these and other socio-economic factors can have an adverse impact on community members’ health, from birth outcomes to life expectancies. Hence, through myriad grassroots partnerships, Hopkins nurses and nursing students are working in East Baltimore to gain a better understanding of residents’ health needs, and to develop ways to meet them where they are.

Cardiovascular disease affects every community. But in neighborhoods where residents lack regular preventive medical care and have limited knowledge of or access to healthy eating habits and physical fitness options, the risks for preventable cardiovascular events increase exponentially. That’s why, at the Lillian D. Wald Community Nursing Center, JHUSON’s first nurse-managed center, East Baltimore residents who are low-income, uninsured, or underinsured receive primary care free of charge.

Two days a week, School of Nursing instructor Mary Donnelly-Strozzo, DNP, MPH, CRNP, conducts basic physical examinations at the Wald Center, blocks from JHUSON at 909 North Broadway. Regardless of what brings them to the center, patients also undergo a Framingham Cardiac Assessment, which predicts a patient’s risk of developing heart disease.

“My goal is to increase the awareness of the risk of cardiovascular disease. Everybody who comes here gets educated; we go through the risk assessment,” Donnelly-Strozzo says.

While finding otherwise undetected cardiovascular risk factors in patients gives them an opportunity to address their health problems, Donnelly-Strozzo benefits by making connections between her hypotheses and her actual findings. “My assumption [prior to seeing patients at Wald] was that there is a huge percentage of underdiagnosed diabetes, lipidemia. I’m finding that’s true,” she says.

While approximately 60 to 70 patients pass through the Wald Center each month, Donnelly-Strozzo knows there are many more residents in the community they could be reaching. She and others at Wald are working to forge community alliances–with multi-family dwellings, churches, and other local entities–to bring messages of health prevention. “It takes time to develop the trust that’s needed to work with various groups in the neighborhood,” Donnelly-Strozzo says.

Phyllis Sharps, PhD, RN, FAAN, also knows this to be true. The JHUSON dean for Community and Global Programs has worked with disadvantaged women and infants in the community, primarily at the House of Ruth, a program that offers shelter to battered women and their children.

“One of the things I’ve noticed in communities of color is that a lot of babies are born too small and too early. I’ve devoted my career to try to figure out what we can do to prevent that,” says Sharps, recently named to the Sigma Theta Tau International Nursing Honor Society’s Nurse Researcher Hall of Fame. “I figured out you have to start long before the mom comes to the hospital.”

Sharps has worked with mothers and pregnant women at the House of Ruth and in their homes. A recent grant from the National Institutes of Health allowed Sharps to conduct a community research project dubbed the Perinatal Home Visiting Enhanced with mHealth, a promising intervention that uses mobile technology to help keep abused women and babies safe from intimate partner violence.

Sights Set on Community Nursing

The prospect of ample opportunities to practice nursing in a community setting excites professionals at the every level of their careers. For some, it shapes career decisions even before they embark on their nursing profession. Such was the case with Molly Greenberg, a student in JHUSON’s new 17-month Accelerated Bachelor’s to MSN program, who considers working in a community health setting her “dream situation.”

“I knew a little bit about the community outreach program (COP). Had Hopkins not had that, I really would have thought twice about applying here,” says Greenberg, who considers COP the most valuable learning experience she’s had at JHUSON.

COP allows students to gain valuable, hands-on nursing experience in a community setting. Interested nursing students must take a prerequisite course about community health nursing and undergo an application process. Those selected work four hours a week at $12 an hour in one of approximately 26 sites in close proximity to JHUSON’s downtown campus. All positions require direct contact with clients or patients. In any given time, about 80 to 100 nursing students are enrolled.

“This is about service-learning, getting engaged in the community, and networking with other health professionals,” says COP co-coordinator Mindi Levin, who also is founder and director of SOURCE (Student Outreach Resource Center) at the Johns Hopkins University Schools of Medicine, Nursing, and Public Health.

COP provides the framework for a reciprocal relationship. The nursing students are responding to community needs and simultaneously gaining valuable experience as part of a team. COP also presents a way of providing nursing care that validates their professional goals.

Through the COP, Greenberg is working at Dayspring Programs, Inc. at Patterson Park Avenue in East Baltimore. The nonprofit offers a transitional housing program for women with previous substance abuse problems and their children. She says she started out just listening, watching, and learning. Recently, her supervisor gave her two clients with whom Greenberg works as somewhat of a case manager. Both have infant sons and need support balancing care for their sons and themselves. “We talk a lot about whether she has a doctor’s appointment and, if so, when will she have time to exercise and how she can get to the appointments she has,” Greenberg says.

The type of relationship she has with her clients, according to Greenberg, is unlike any she’s had at, say, a clinical rotation in a hospital. Here, it’s a team approach and she and the client work together toward a common goal. “It’s a different kind of nursing, the kind I want to provide. And hopefully, it’s the way the health system is going to go,” she says.

“These women are dealing with so much. Sometimes they just want to laugh,” Greenberg says. “A lot of them might be homeless if they weren’t here.”

Full Circle in East Baltimore

Linda Whitner knows that feeling all too well.

Back in 1994, Whitner was working to pull her life back together. Having overcome addiction two years earlier, she and her children took shelter at the Lanvale Transitional Housing Program on East Baltimore’s Rutland Avenue, similar in many ways to Dayspring. A clerical job at the Wald Clinic, then housed on the first floor of the transitional housing program, helped turn Whitner’s life around.

The late Marion D’Lugoff, founder of the Wald Clinic and a JHUSON assistant professor, hired Whitner and other residents to do clerical work. Whitner excelled. But as was the policy, once residents received a Section 8 voucher–which usually took upwards of a year–they relinquished their spot at the transitional shelter to make room for an incoming resident. Whitner got the voucher but kept the job.

Whitner believes that D’Lugoff saw in her someone who showed interest, took initiative, and related to the clients. Whatever the case, D’Lugoff made it possible for Whitner to remain as a resident at the shelter a bit longer and continue to work part time at the Wald Clinic. In October 1995, Whitner moved into her own apartment. In 1998, she accepted full-time employment at the Wald Clinic.

Flash forward to 2013. Whitner continues to be an integral, full-time member of the Wald Clinic’s staff. As a clinical outreach coordinator, she does everything from counsel clients in need of various health programs to run smoking cessation programs. At the encouragement of her co-workers, she obtained her bachelor’s degree in social work in 2011 and is eyeing a return to school to begin work on her master’s. She is 61 and has the energy of someone much younger.

Having found success in large part because of a JHUSON community health nursing program, Whitner is now helping others reach their potential. “Initially, I counsel clients. A lot of them have personal matters going on,” Whitner says. “I listen. That’s first and foremost.”