Palliative Care Offers Benefits for Patients, Families, and Healthcare Professionals Alike

by Rebecca Proch

When the physician called Robin Lewis-Cherry, BSN, to ask her to approve dosages of Ativan for her chronically ill mother, Robin realized her mother was dying. She approved the treatment and hung up, and her eyes fell on her binder of material from the End of Life Nursing Education Consortium (ELNEC) certification course she was in the midst of completing. “Literally the first thing I did,” she recalls, “was to reach for that binder and thumb through it.”

They had just covered in class the signs of physical deterioration that signal the end of life. Robin, a nurse in Nelson 3, was seeing her mother pass through this process even as her instructors presented it, the material hitting home in a deeply personal way. The course had started out as something that all members of Johns Hopkins’ cross-departmental Nurse Palliative Care Committee were taking, but it had become a guide, walking her through the unexplored territory of her own grief. She found herself turning again and again to the resources of this training not only for her work, but also for her own support.

“I was grateful to have it,” she says. “I was able to understand how my mother’s condition was progressing, and I was better prepared to make the decisions about her care that would make her more comfortable.”

Enriching Patient Care

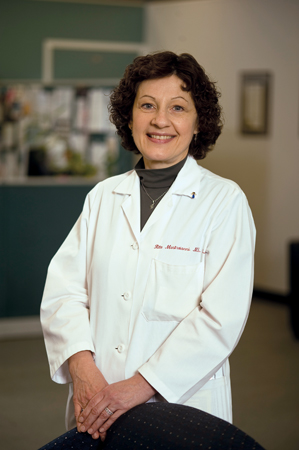

Rita Moldovan, DNP, RN, a Clinical Nurse Specialist who works in Palliative Care in Johns Hopkins’ Department of Medicine Nursing, was the one who had invited Lewis-Cherry to join that committee. She herself was drawn to palliative care before there were any formal programs in place at Johns Hopkins. She recalls working on the night shift early on in her three decades of nursing, when she would have more time to sit with patients who couldn’t sleep and to talk with them about their fears and the things they struggled with.

She saw a need. Over the past eleven years, her work has focused on making palliative care an integral part of the patient experience at Johns Hopkins, not only for terminal patients but also for those whose conditions are curable.

Although it includes hospice and end-of-life care, Moldovan emphasizes its benefits for all patients, especially at this point in time. “Healthcare has become so complex,” she says. “There are so many options and factors to consider. Patients are at their most vulnerable, and making decisions can feel confusing and overwhelming.”

Lynn Billing, RN, CHPN, B-C, agrees. As Nurse Coordinator with the Duffey Pain and Palliative Care Service in the Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center, she is face-to-face with these realities every day. Duffey’s interdisciplinary team—which includes a nurse, a physician, a pharmacist, a social worker, a chaplain, and others—receives new referrals almost daily. “Our job is to take as much time as needed to make sure the patient really understands everything about their situation. We need to be sure we’ve helped them frame and determine their goals in a realistic way while honoring their hopes and dreams.”

“We can help patients and their entire team look beyond the immediate moment and make decisions about the big picture, whatever that looks like for them,” says Moldovan, adding that her first questions in a palliative care situation are always, “What do you know? What do you hope for?”

Family Matters

Palliative care always involves the patient’s family, whether that’s discussing with a patient their anxiety about being a burden on their loved ones, or providing support directly to family members who may experience burnout and fatigue in their roles as caregivers.

Lewis-Cherry recalls how glad she was that she accepted the offer of palliative care from the team at the University of Maryland Medical Center during her mother’s final weeks. The team’s physician talked with her and her brother about their mother’s wishes and helped them sort through the options for interventions with that in mind. “I felt validated in my choices,” she says. “It helped to hear him say that he agreed with what we wanted to do.”

Moldovan finds it very useful to seek out one family member who really “gets it” and to allow them to be a liaison between hospital staff and the rest of the family. Billing adds that different members of the Duffey team tend to have their specialty when it comes to families—one may excel at talking with young children, while another may relate best to grandparents. It can be essential to draw on the strengths of the whole team to talk to family members, sometimes separately, and discover what’s at the root of their beliefs.

Team Effort

When a palliative care team is called into a situation, they may find that they need to mediate disagreements among the patient’s care providers about the best course of action. Says Moldovan, “We try to work with the patient’s team to get everyone to a point of agreement, and one of the things we’re constantly educating about is how to weigh the burden of a particular intervention against its benefits.”

The team always strives to form an alliance with the patient’s care providers, not to supplant them. They are able to take the time with the patient-family unit that the staff’s workload may not permit. They can bring perspective and offer validation for providers’ decisions or bridge communication between the providers and the family.

Moldovan based her doctoral work on her observations of the need for more widespread and structured implementation of palliative care within Johns Hopkins. Out of that work emerged her current project, the establishment in 2010 of the Nursing Palliative Care Committee. Formed in collaboration with Deborah Dang, PhD, RN, the Director of Nursing Practice, Education and Research at Hopkins to examine the issues around palliative care, their chief goal is to develop and implement a framework that will educate and empower all nursing staff to better provide this care.

The committee, made up of nurses from all departments within Johns Hopkins, meets once a month for two hours. Their first two years’ priorities are to ensure that all members take the ELNEC certification course and to create protocols and nurse competencies that will be shared with all nursing staff. Moldovan believes the certification and protocols will give bedside nurses the tools they need to more confidently identify and serve the best interests of the patient in all situations.

Addressing Nurse Suffering

One of the issues that Moldovan believes the committee will tackle down the line is that of nurse suffering and resiliency. She would like to see outcomes evaluations and studies that result in recommendations for support resources on an organization-wide basis. The emotional and spiritual impact of the work on nurses, particularly in end-of-life situations, is something that she does not feel is fully understood or consistently addressed across the organization.

It was a topic that the committee discussed on the day Robin Lewis-Cherry’s mother was buried. At the next meeting, they asked Lewis-Cherry if she would like some time to talk with them about her experiences and her grief, and they invited her to read the poems she had written for each of her parents’ memorials.

From that point on, the committee decided to designate the first fifteen minutes of every meeting to a debrief session. Every member has the opportunity to share their thoughts and experiences, to talk about their sorrow when they’ve lost a patient, and to recount the stories they might otherwise have no place to tell. “We need to make time to support each other,” says Moldovan. “If the well is dry, we have nothing left to give.”

Billing sees this healing emerge organically every time she facilitates the ELNEC course. The nurses who participate have often dealt with end-of-life situations, and the interactive nature of the course gives them the opportunity to talk with each other about their experiences and to share their feelings. “It helps to know that you’re not alone in what you’ve been through,” she says.

Lewis-Cherry is glad to draw on her experiences and training to support her colleagues. “A lot of nurses don’t have an outlet at work because there’s so much to do,” she points out. When a fellow nurse came to her seeking guidance about dealing with the death of a close family member, Lewis-Cherry was able to give her concrete advice to help her manage the specifics of the situation.

This is, Moldovan says, at the heart of palliative care—a focus on tangible, practical, everyday actions that a patient, their family, and their care providers alike can take to improve quality of life. The essence of her philosophy is simple: “No matter what, there is always something we can do to help.”

Learn more about the ELNEC certification course at www.nursing.jhu.edu/elnec.com