Earlier this week I spent four hours on the phone with immigration for a battered mother whose abusive husband had stopped filing his half of the paperwork for her green card. I wish I could say that this story was unusual; it’s not. She rocked her infant lightly in her arms while I ran through the automated menus of a dry, impersonal USCIS information line.

“Are you the client’s official translator?” I was asked when I finally got to an (equally impersonal) operator.

“Sure,” I replied. That was a close-enough description of what I was doing: helping a woman with accented English navigate a maddeningly complicated system of endless paperwork and fuzzy phone lines. More accurately, though, my afternoon fell under the ever-broadening territory of what it means to be a nurse.

Every week I spend four hours working at the House of Ruth, a domestic violence shelter. This work is through the JHU School of Nursing Community Outreach Program (COP), a service-learning collaboration between the SON Department of Community-Public Health Nursing, the Student Outreach Resource Center (SOURCE), and various community organizations. Those of us in the COP take a course, apply to various worksites, and then make a yearlong commitment to our placements, getting paid for our time through the financial aid or the business office. It’s experiential education, work-study, and a community health apprenticeship, all rolled into one.

When I first showed up at the House of Ruth, I was worried that I wouldn’t be able to contribute. As a first semester student, there’s a lot that I can’t do. I can’t help the mother who comes down to the House of Ruth’s health suite and asks if I can check out her daughter’s ear infection. I can’t give medications, or do a qualified assessment. While these are all skills that I’m learning in school, I’m just not certified to apply them independently yet. But as my preceptors pointed out on my first evening at the shelter, there is a lot more to nursing at a domestic violence shelter than checking people’s blood sugar and evaluating an ear infection. Just as there is a lot more to health than just medicine.

Imagine that you have finally left your abusive partner, along with your home and many of your possessions. Maybe your situation was dangerous enough that you arrived at the shelter in a police car that had been sent to your apartment while he was at work. You are given a room in a shelter filled to capacity with other abused women and their children. You have 21 days to figure out what to do next. Are you pressing charges? How are your kids getting to school? Where will you find housing, and who will rent to you when your last 4 leases were broken as you fled, again, from your abuser?

These are all good questions for social workers, lawyers, and other non-nursing professionals. But there is a lot that a nurse can do here, too. “I like to walk around the hall and introduce myself to new arrivals,” said one of my preceptors, an RN and JHU master’s student. A lot of the time, women are dazed and overwhelmed when they first arrive. Sometimes they just need someone to talk to. “And sometimes they just need someone to talk to them about something besides being a victim of domestic violence,” she pointed out.

There are eight of us nursing students working at House of Ruth this year. Two women organize afternoon walks, an opportunity to get women outside, exercise, and chat about everything from the blissfully mundane to pressing worries. Others help out at the daycare center, playing with the children while simultaneously evaluating their development. Around mid-afternoon, the school-aged kids come “home” from school; nursing students help tutor them and encourage them to get their homework done. Another nursing student taught an evening yoga class, and ideas for nutrition classes are in the works. While none of these interactions involve stethoscope or a blood pressure cuff, they’re all part of a larger effort aimed at improving the health—physical, mental, and social—of the women and children staying at House of Ruth.

I’m in the process of helping a woman sort out the question of her citizenship in the United States. Perhaps, as a nursing student, I should be asking her more about her body—how are her lungs, her heart? Do her feet hurt, or her fingers ache? I have no idea. But could you concentrate on finding a primary care doctor when you might be deported? And what will be more detrimental to your health, delaying a full check-up, or finding yourself homeless when your stay at the Emergency Shelter is over? I hope to get the chance to see her sitting on an examination table, her blood pressure taken and heart listened to. But I understand that my role as a nursing student can encompass these other issues—issues that are in and of themselves barriers to health—as well.

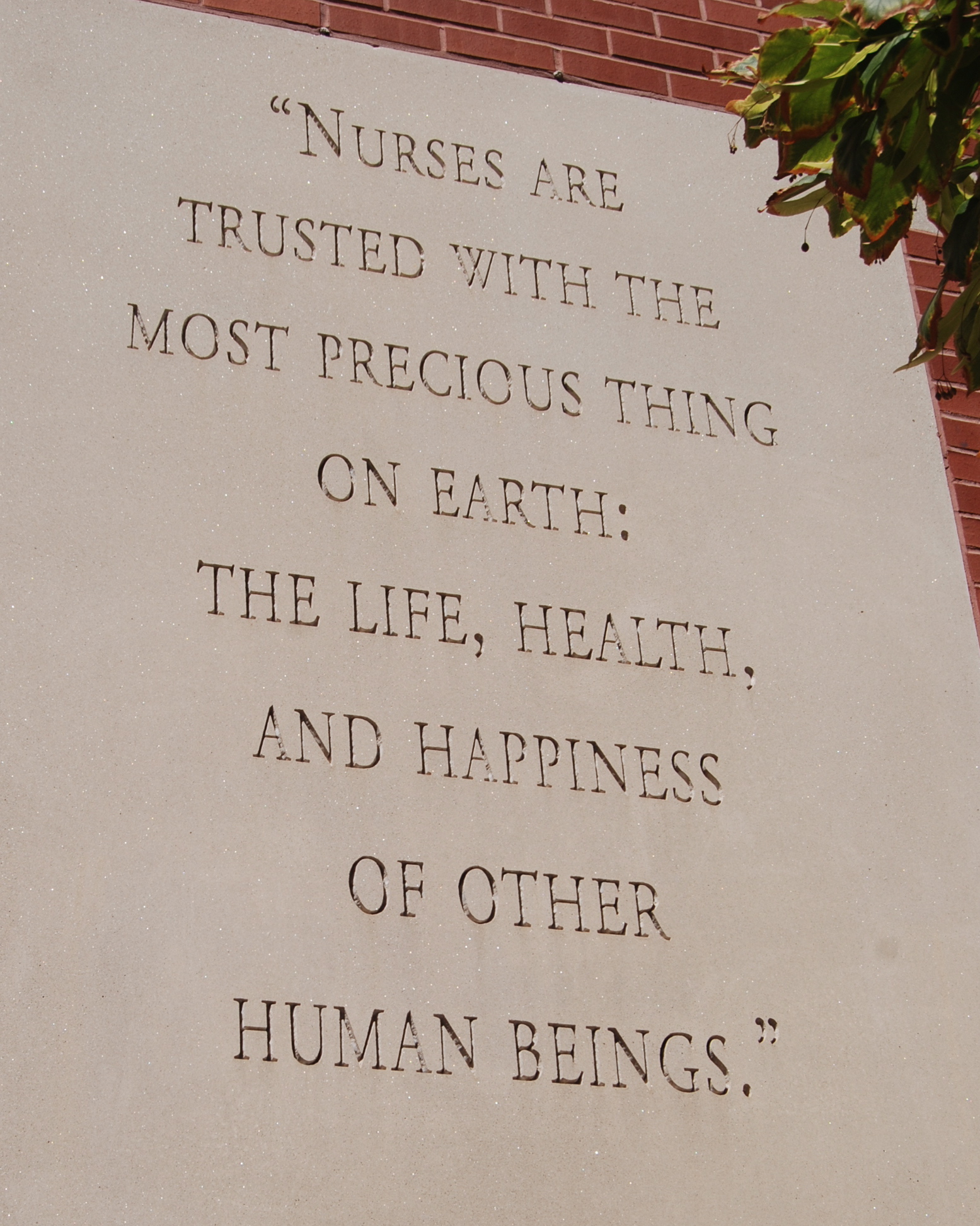

Every day I walk past an inscription on the side of the JHU School of Nursing, a 1902 quote from Isabel Hampton Robb: “Nurses are trusted with the most precious thing on earth: the life, health, and happiness of other human beings.” In the century since Robb’s quote, the depth and breadth of that job description has only grown.