Give nurses a voice and provide opportunities for growth

By Stephanie Shapiro

Illustrations by Jon Krause

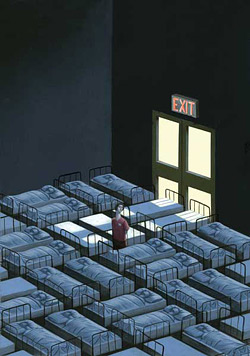

On those rare occasions at The Johns Hopkins Hospital (JHH) when Osler 4’s staff schedule clicked smoothly into place, peace of mind was inevitably short-lived for nurse manager JoAnn Z. Ioannou, MSN, MBA, RN.

“Right when you think things are going to be consistent, someone will walk in on Monday morning to say they’re leaving,” Ioannou says.

And once again, her meticulously constructed schedule would become a casualty of a nursing shortage that plagues hospitals and health institutions nationwide.

For nurse managers, constant staff reshuffling “is very stressful because there are so many things they have to balance,” says Ioannou, now JHH assistant director of medical nursing.

For example, “When you have a lot of agency nurses compared to regular staff, patient satisfaction might go down as well as patient care. You might have more errors,” Ioannou says. She also had to factor in that an unwieldy ratio of agency nurses to permanent staff could harm morale.

The nursing decline impacted other aspects of Ioannou’s job as well. She often had to ask experienced unit nurses to precept new hires, a time-consuming chore on top of other responsibilities. And she frequently faced the painful task of weighing budget concerns against the welfare of her patients.

“It’s a constant struggle,” Ioannou says. “When you look at the global picture, the supply and demand is going to dictate how long we’re in this predicament. It’s daunting when you think about it.”

And yet, her enlightened management style kept Osler 4’s vacancy rate below 10 percent, compared to the 13 percent state average. “You have to invest in your staff and give them what they need to deliver the best care,” says Ioannou, herself a candidate in the new doctor of nursing practice (DNP) program at the Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing (JHUSON).

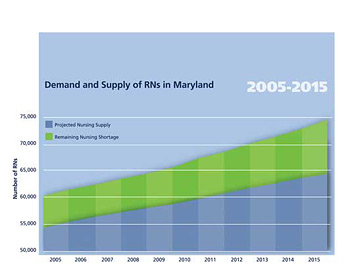

Hospitals throughout Maryland, around the country, and in many parts of the world confront a severe shortage of qualified nurses. The United States could face a deficit of as many as 500,000 nurses by 2025 according to The Future of the Nursing Workforce in the United States, a report released in March by Peter Buerhaus of Vanderbilt University School of Nursing and colleagues. Without additional funding, Maryland’s nursing shortage could balloon to more than 10,000 registered nurses by 2016 according to Who Will Care? The Case for Doubling the Number of RNs Educated in Maryland, a 2007 report by the Maryland Hospital Association (MHA).

Nationally, an untimely convergence of factors is fueling the prolonged and mounting nursing shortage. Population growth, aging baby boomers, and labor-intensive medical advances have all contributed to the crisis, as will the impending retirement of more than 40 percent of the nursing workforce.

The scarcity is compounded by the national penchant for mobility, professional aspirations beyond the bedside, and the stress of working in a managed care environment. And long-term fixes may be hard to achieve as nursing schools do not have the resources required to educate enough nurses to meet the need.

Without concerted intervention by hospitals, nursing schools, public officials, and others, the demand for nurses will far exceed the supply, experts say.

“In Maryland, there are more nursing positions budgeted than ever before and more nurses working than ever before, and at the same time, the nursing shortage is increasing,” MHA vice president Catherine M. Crowley, EdD, told a group of Hopkins faculty and nurses in April.

Through a host of initiatives, Hopkins nurses are playing a prominent role in the effort to resolve the nursing shortage both within and far beyond their workplace. Their strategies range from the grand – recommendations for profound institutional changes – to the small-bore, such as a Jonas Nursing Scholar award for a PhD student committed to teaching fledgling nurses in the New York City area. And they also take into consideration the disparate needs of a multigenerational workforce.

Many of these efforts share Ioannou’s philosophy: Give direct-care nurses a voice and provide opportunities for growth, and they’ll stick around longer.

How to Make a Hopkins Nurse a Happy Nurse

Funded by Nurse Support Program (NSP) grants from the state of Maryland, Hopkins nurses are exploring a variety of approaches for improving retention among new and experienced nurses.

When a nurse arrives in a new unit, the flood of information that must be absorbed in a high-acuity setting can discourage the most enthusiastic novice, says assistant professor Janice J. Hoffman, PhD, RN, CCRN.

Hoffman is developing a three-year preceptor program focused on teaching and learning strategies that will enhance critical thinking and confidence at the bedside.

Named INSPIRE (Inform, Nurture, Support, Promote, Instruct, Role Model and Encourage), the program provides ample time for discussing patients, reviewing protocol, and performing exercises in the new JHH Simulation Center. More than “just skills,” the pilot preceptor program allows new graduates the luxury of “really understanding,” Hoffman says.

Does a direct correlation exist between retention and critical thinking skills? “We’re not sure,” Hoffman says. “Based on why we know new graduate nurses leave,often they’re not comfortable in their unit or they get overwhelmed.”

Another NSP-funded effort tackles the volatile emotions that can surface under stressful working conditions. Researchers have documented recurring patterns of verbal abuse and condescending treatment “all the way up to violence,” notes assistant professor Jo M. Walrath, PhD, MS, RN. She is a co-investigator on a study at JHH designed to yield strategies for confronting disruptive workplace behavior. The goal is to prevent nurses from becoming disenchanted and leaving the organization, Walrath says.

To achieve the fulfilling and stimulating work environment that guarantees excellence in patient care, experienced nurses as well as novices need the support provided by mentors, says SON assistant professor Susan Immelt, PhD, RN. With an NSP grant, she collaborated with the education and administrative team at Mt. Washington Pediatric Hospital to create a five-year program to improve nurse retention in the pediatric rehabilitation facility.

The project reinforces the specialized skills required for a range of delicate tasks, from tending children who have suffered from traumatic brain injuries to educating families who will care for their sick infants at home. In addition, nurses in the program learn to work as a team in problem-solving in patient care and managing emergencies.

Retention can be particularly difficult in a unit with extreme emotional demands. In her pediatric-oncology unit at JHH, nurse manager Lisa M. Fratino, MSN, RN, places equal emphasis on the staff’s psycho-social and clinical capabilities. “Maintaining resiliency is really the key to our success in retention over the last few years,” says Fratino, who worked with associate professor Cynda H. Rushton, PhD, RN, FAAN, and bereavement coordinator Elizabeth Reder, MA, to strengthen the unit’s coping skills.

A mentoring program, retreats, celebratory dinners, informal debriefing opportunities, and grief counseling have all contributed to pediatric oncology’s impressive vacancy rate. “The key is to support them and to support resiliency at work and to hopefully find strategies to keep their cups filled so they can come back each day,” Fratino says.

As co-chair of the Central Nursing Recruitment and Retention Advisory Committee, Fratino is drawing on her expertise to help lower the vacancy rate hospital-wide. At committee meetings, the opinions of direct-care nurses are as highly regarded as those of their super-visors. After a study of best practices around the country, the committee plans to make a number of recommendations to the hospital for engaging today’s multigenerational workforce.

Other retention efforts designed by Hopkins nurses have a proven track record.

Now in its sixth year at JHH, the SPRING (Social and Professional Reality Integration for Nurse Graduates) program has more than paid for its expense by retaining scores of anxious new grads.

“We have an 85 percent hospital-wide retention rate, versus 65 percent nationwide,” SPRING nurse educator Sartorius-Mergenthaler says. “SPRING was designed to help new graduate nurses transition into their new community through the process of socialization and professional development,” she says. “Strengthening the skills of critical thinking, safety, and competence instills the confidence new graduates need to do their jobs.”

New nurses, themselves, bring a more global, technologically sophisticated perspective to the workplace that must be validated by their mentors, Sartorius-Mergenthaler says. “They are teaching us what they need and what kind of program they want. It is a partnership.”

A parallel JHH program called PEDS (Pediatric Education Development and Support) assists newcomers who are navigating an unfamiliar environment while mastering a profusion of skills.

At Howard County General Hospital, a member of Johns Hopkins Medicine, the Bridging the Gap program also supports new grads on the journey to professional nursing. In November, an NSP grant provided the program with a resident mentor, Vera Tolkacevic, MBA, RN. “We would like for her to be recognized as the big sister’ to the novice nurses,” says director of clinical education Blanka McClammer, MA, RN, NEA-BC.

On the far end of the career span, experienced nurses with retirement on their minds can provide a partial solution to the nursing shortage. “We are looking really hard at how we can keep our older nurses active in the field,” says Sharon P. Hadsell, RN, MSN, NE-BC, the hospital’s senior vice president of patient care services.

The hospital has also launched a marketing plan to recruit more part-time employees and to encourage veteran part-timers to add shifts, a campaign that might get a boost during the current economic downturn.

In Maryland, Nurses are “A Piece of the Solution”

The same workplace values advocated by nurses within Hopkins underpin their external retention efforts. Three teams from JHH and one from the Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center are part of an initiative to attain a 95 percent nurse retention rate in participating units from 19 hospitals across Maryland.

This effort, known as the MHA Nurses Retention Collaborative, seeks to establish “new ways of working.” By fostering a work environment that empowers nurses, job satisfaction grows and burnout wanes, according to the guiding premise of the collaborative.

Each of the collaborative’s 28 teams, composed of nurses from hospital units across Maryland, has been assigned the task of refining or creating a new approach to a particular problematic process on their nursing unit, such as medicine delivery or designing a protocol for safely lifting patients. The goal is to use the front-line nursing staff to improve the process.

Once an innovation proves successful, it will be disseminated more widely, says Jo Walrath, JHUSON assistant professor who served on the expert panel that established the groundwork for the collaborative.

As they develop and implement more effective strategies, nurses also realize that they are “a piece of the solution,” Walrath says.

Carol Miller, BSN, RN, CCRN, the patient care manager for Johns Hopkins Bayview’s surgical intensive care unit, is leading a team for the collaborative that is targeting shift-to-shift communication gaps.

Her staff has responded enthusiastically, Miller says. “There is so much focus on recruitment and nurses [often ask], When is anyone going to listen to why I don’t want to stay in the nursing profession?'” Miller says. “They are really excited that we want to listen to them and implement strategies to help them stay here. It’s a really different focus.”

Through another state-wide initiative, the Maryland Nursing Workforce Commission, one Hopkins researcher is looking at technology’s potential to compensate for the nursing shortage. Maria V. Koszalka, EdD, MA, RN, Johns Hopkins Bayview vice president of patient care services, has emerged as a staunch advocate for incorporating high-tech tools into the workplace.

As a Commission member, Koszalka and her co-authors produced a report that champions the judicious introduction of advanced technology to streamline daily tasks and enhance patient safety.

Success “really depends on the maturity of the hospital in the implementation of technology early on,” Koszalka says. “At first, it is a cumbersome, time-consuming, frustrating process. After nurses become accustomed to it, they can’t live without it.”

To embrace new technology, nurses must be involved from the start, Koszalka says. As a bar coding system for medication administration is being introduced at Johns Hopkins Bayview, every nurse has been invited to test and evaluate the new equipment, she says.

Need More Nurses? Educational Resources are Vital for the Future of the Nursing Workforce

To a large extent, widespread faculty vacancies, salary restraints, and insufficient classroom space are an underlying cause of the nursing shortage. The MHA report found that 1,850 qualified nursing candidates were turned away from Maryland’s colleges and universities in 2006 because programs were full.

On a national scale, according to a survey by the American Association of Colleges of Nursing, 40,285 qualified nursing school candidates were turned away from baccalaureate and graduate programs in 2007 because of insufficient faculty numbers.

A sense of empowerment will only go so far to stem the nursing shortage without a steady infusion of new graduates. Enrollment must double in order to meet Maryland’s nursing needs in 2015, says MHA’s Crowley. That means more classrooms, teachers, support people, and graduate assistants at an estimated cost of $135.5 million over a five-year period.

As nursing staff, administrators, and researchers find more ways to cultivate a stable nursing staff, Karen Haller, PhD, RN, FAAN, is thinking about the future.

“The hospitals have worked dili-gently to improve the quality of the workplace and to attract and retain our nurses,” says the JHH vice president for nursing and patient care services. “Salaries have improved, benefits have improved, but the pipeline isn’t opening.”

The shortage boils down to funding and is not “fixable by any one institution,” Haller says. “We’re going to need a collaborative approach to this problem.”

She says MHA’s call for funding to increase the number of first-year nursing school students in Maryland by 1,800 in fall 2009 is the right approach. “The strategy at MHA,” she adds, “is to get private money to jumpstart the process and then go back to the hospitals and say, We need you to step up to the plate.'”

In the meantime, the School of Nursing is making the most of its resources to produce more graduates. Since opening its doors in 1984, the school has seen student enrollment grow to an average class size of 140. Efforts to prime the nursing pipeline include the school’s accelerated baccalaureate program, which has become a model nationwide for fast-tracking new graduates into the workforce.

A recently introduced MHA innovation that identifies and schedules clinical sites has significantly expanded the school’s capacity for training nurses. Called Clinical Assignments for Healthcare Students (CAHS), the automated scheduling system is available to all Maryland nursing schools. It is administered at JHH by project analyst Kelly Reif, RN.

“There are units that may be available to schools that weren’t being used before,” says Reif, who helped to set up the CAHS system. “CAHS allows schools to see what is available at each hospital, and to possibly create a relationship they might not have had in the past.”

Not only has the collaborative program found much needed space for clinical training, it has drastically reduced scheduling time. “It also provides information on the overall capacity of the state to accommodate students,” Reif says.

With the construction of an eight-story addition over the next decade, the School of Nursing will have the capacity to accommodate more teachers, students, and researchers. As reflected by the MHA report findings, though, salaries remain a barrier to filling those new classrooms, says Dean Martha N. Hill, PhD, RN, FAAN.

There is a “huge gap” between faculty salaries and those earned by nurses in critical care settings, government positions, and other fields, Hill says. To retain and attract faculty, “You strip all the fat out of your budget and you operate in a very conservative fiscal environment,” she says. Such steps have allowed JHUSON to maintain faculty salaries among the highest 25 percent nationally.

Currently, the dean’s plans for growth are concentrated on “the business of preparing leaders for the future” within the school’s graduate programs.

Several existing graduate programs were designed with the intention of producing teachers as well as researchers and clinicians. The PhD program began in 1993, and so far, 29 students have graduated. “We prepare nurse scientists. Many of them go into academic nursing,” says program director Marie T. Nolan, MPH, PhD, RN.

“We have recruited students directly from the baccalaureate program in order to move students more quickly,” Nolan says. It’s a way to afford PhD students more years of productivity as researchers and educators.

Supported by an NSP grant, the School of Nursing launched its doctor of nursing practice (DNP) program in the spring of 2008 with the aim of producing more expert nurse clinicians, leaders, and administrators. The DNP is also a conduit for increasing joint appointments between the school and JHH, Janice Hoffman says. “That’s where a lot of our future faculty are going to come from.”

For interim DNP director Kathleen White, PhD, RN, CNAA, BC, one of the program’s values rests in its potential to create a more supportive and effective work climate, a crucial element in reducing attrition. Doctorally-prepared clinicians who continue to work in our hospitals “will increase the quality of the practice environment,” she says. “That makes not only for more satisfied new grads, but more satisfied staff, period, and hopefully more satisfied patients.”

Low Band Width to Fight Brain Drain

by Stephanie Shapiro

In a community just south of the Arctic Circle where no doctors practiced, two Inuit traditional health attendants e-mailed a question to an online community for nurses and midwives around the world.

The health care providers asked for suggestions on how to encourage best practices for diabetic management among their native population.

Among the 20 responses from around the world came one from a remote corner of Bolivia. “It was a totally different hemisphere, with an entirely different culture, but the problems faced by the care providers were remarkably similar,” says Assistant Professor Patricia Abbott, PhD, RN, FAAN, FACMI. Within the electronic Community of Practice forum, “geography is irrelevant,” says Abbott, who runs the online resource.

Launched in 2006, the Global Alliance for Nursing and Midwifery Community of Practice (GANM CoP) is one way of grappling with a global nursing shortage felt most acutely in developing nations.

According to a 2004 report led by the International Council of Nurses (ICN) and the Florence Nightingale International Foundation (FNIF), nations in Africa, Asia, and Central and South America struggle to achieve a minimum level of nurse staffing. Already inadequate, nursing populations in those countries have been drained further by migration sparked by the international recruitment industry.

Initiatives such as the GANM CoP help to reduce the “pull factors” that lure nurses and midwives away from remote locales. Requiring very low bandwidth, the GANM CoP is available to practitioners in the world’s most rural outposts and provides a growing repository of instructional information and a communication life-line to others around the globe.

As a result, a nurse midwife from Burkina-Faso seeking more training, for example, won’t necessarily attend school in Europe and decide to stay, only to exacerbate the nursing shortage in her native country, Abbott says. “This is incredibly cost effective,” she says. “We can deliver the education to them, impacting the quality of services they provide and empowering them by connecting them and giving them a voice.

The online community is not a panacea, though, Abbott says. “The issues of poor working conditions, safety and general poverty require concomitant attention.”

So far, more than 1,500 nurses and midwives from 124 countries have become part of the GANM CoP, which is operated through the school’s PAHO/WHO Collaborating Center for Knowledge, Information Management, and Sharing.

Demand-side Economics: Explaining the Nursing Shortage

by Karen Haller

Working to recruit and retain the best nurses is necessary to ensure the availability of professional nursing services for our patients. Solving the shortage is, in part, about the supply of nurses. But attenuating the demand for nurses is also needed.

Let’s roll back the calendar to the year 2002: At The Johns Hopkins Hospital, we had a budget to support 1,550 nurses. All positions were filled with regular staff, float pool, or temporary nurses hired from an outside agency.

Fast forward: Today, Hopkins has 2075 RN full-time-equivalents (FTEs) on staff. That’s 525 more than the 2002 budget. It looks like we have an excess number of nurses on board! Nursing shortage? What shortage?

The reality is that the number of nursing positions at Hopkins has grown about 85 FTEs per year. The nursing shortage is not so much a result of high turnover and inability to recruit, but an inability to keep up with growing demand for nursing services.

What’s fueling the demand? The patients in our hospitals are sicker than ever before, and they continue to be discharged within a quicker time frame. Managing the patient acuity and the intensity of hospital admissions requires additional staff. The new infections resistant to current antibiotic therapies require extensive isolation procedures (which take time).

Regulatory requirements, such as medication reconciliation at each transfer of care, create new work which takes significant time to do and document. A new 80-hour work-rule for interns and residents caused work to shift to nurses who, on many units, have taken on additional responsibilities for facilitating rounds and expediting patient care. And though technologies have made our hospitals safer and more effective, they have not helped nurses save time.

In short, while we look to the supply-side to ease the shortage; the demand-side drives the problem.

Big Trouble in Beijing, China?

New nurse educators will help alleviate the country’s nursing shortage.

by Stephanie Shapiro

Although it is difficult to gauge the extent of the nursing shortage in China, there are signs that it could have a troubling impact on the country’s health care system. Elizabeth (Ibby) Tanner, PhD, RN, Assistant Professor at the Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing (JHUSON), recently conducted a geriatric patient care needs assessment at Peking Union Medical College School (PUMC) in Beijing.

Although it is difficult to gauge the extent of the nursing shortage in China, there are signs that it could have a troubling impact on the country’s health care system. Elizabeth (Ibby) Tanner, PhD, RN, Assistant Professor at the Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing (JHUSON), recently conducted a geriatric patient care needs assessment at Peking Union Medical College School (PUMC) in Beijing.

The dearth of nurses wasn’t apparent within that setting, but Tanner’s research suggested that China’s aging inhabitants could sorely test the country’s future capacity to care for many of its most vulnerable citizens.

“Without the appropriate social infrastructure and the ability to address population changes,” Tanner says, “there will be a huge burden placed on the nursing population.”

JHUSON’s commitment to supporting nurses in their home countries led to a pioneering collaboration launched in 2004 with the PUMC school of nursing. The program, funded by the China Medical Board of New York, will increase the number of doctorally prepared nurses in China and develop a nationally recognized doctoral-level model for nursing education.

In July, the first of 15 candidates completed the program and became the first nurses to graduate from a Chinese university with a PhD in nursing.