By Jim Miller

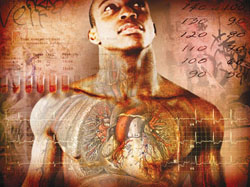

Illustration by Alicia Buelow

Controlling hyper-tension among African American men living in urban areas has long posed a challenge. Many in this high-risk group are without a regular source for hypertension care “and the perception was that they would be difficult to engage and follow,” notes School of Nursing faculty member Cheryl R. Dennison, PhD, CRNP.

Now, Dennison—with School colleagues Miyong T. Kim, PhD, RN, principal investigator Martha N. Hill, PhD, RN, and others—has conducted a hypertension clinical trial specifically targeting high risk, under-served young, urban African American men. The results of the study appeared in the February issue of the American Journal of Hypertension.

The five-year randomized clinical trial compared two interventions for treating hypertension in 309 hypertensive African American men from urban Baltimore. A more intensive approach provided participants with an array of high blood pressure care and social support services supplied by a nurse practitioner, community health worker, and physician team. This group received free antihypertensive medication, nurse practitioner clinic visits, annual home visits by the community health worker, and referrals for social services. The less intensive group received educational information and referral to hypertension care sources in the community. Both groups received education about hypertension care, calls from a research assistant every six months, and annual research visits.

| Fifty-three men died during the course of the study, more than half from narcotic or alcohol intoxication or cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease. …“The high mortality rate in this group of young men illustrates a major societal and public health problem,” notes Dennison. |

The good news: Both approaches succeeded in reducing blood pressure. Each group showed improvements both in systolic and diastolic blood pressure and in the blood pressure control rate at most points from the beginning of the study to the end. Not surprisingly, those who received the more intensive intervention showed greater improvements in blood pressure control than their counterparts who did not. Over the five-year course of the study, men in the more intensive group achieved systolic blood pressure reductions of 4 to 10 mm Hg below their baseline average of 147 mm Hg. Diastolic improvements ranged from reductions of almost 5 to more than 12 mm Hg below the baseline average of 99 mm Hg).

The less intensive group achieved smaller improvements—the best reduction in systolic blood pressure was 3 mm Hg below the baseline average of 148 in the same time period, and diastolic reductions varied from just under 2 to almost 9 mm Hg below the baseline average of 99 mm Hg.

Participants were between 21 and 54 years of age. Some 71 percent earned less than $10,000 per year, 58 percent had never married, and 64 percent had been incarcerated. The study had a high attrition rate, primarily due to death and incarceration. Fifty-three men died during the course of the study, more than half from narcotic or alcohol intoxication or cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease.

“The high mortality rate in this group of young men illustrates a major societal and public health problem,” notes Dennison. But there were hopeful signs as well. With the exception of those who died or were incarcerated, study tracking and follow-up rates were exceptionally high, exceeding 89 percent of available men during five years.

Dennison and colleagues were buoyed by the high follow-up rates and the success in reducing blood pressure among a high-risk group facing a host of societal and economic challenges. But, cautions Dennison, “to achieve sustained blood pressure improvement and reduction and prevent premature death in this high risk population, we must address not only hypertension care issues but social and economic challenges such as substance abuse, unemployment, and lack of insurance at the policy level as well.”