By Jim Paterson

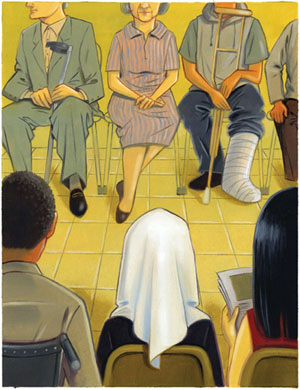

Illustration by Michelle Chang

Disparities in our nation’s health care system have dire health consequences for minorities and the poor. Meet a variety of Hopkins nursing researchers who are committed to finding solutions.

A close look at the American health care system reveals a sobering reality: Health problems disproportionately affect minority and poor members of our society. Consider, for example: Diabetes and high blood pressure are more common among Korean Americans, gonorrhea is 19 times more prevalent among African Americans, and women in lower socio-economic levels have a greater incidence of cardiovascular disease than their counterparts with more resources.

“We’re trying to find out what can be done,” says Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing’s Fannie Gaston-Johansson, PhD, RN, FAAN. “It might involve the waiting times for medical appointments, or health insurance, or access to care. It can even just simply involve patients being able to communicate with someone who understands them.”

Gaston-Johansson is director of the Center on Health Disparities Research, a partnership between the Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing, the National Institutes of Health, and the North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University School of Nursing. The four-year-old center currently has 13 funded pilot projects under way. All are aimed at finding effective measures to close the trouble-some and sometimes startlingly broad gaps in our nation’s health care system.

“It is very costly to have health care disparities,” says Gaston-Johansson, noting that many related health crises are the result of patients not receiving appropriate “education, preventive care, or timely treatment.” She adds, “The emergency room is not the place to provide health care.”

In addition to the pilot projects funded by the CHDR, there are a variety of other health disparities research efforts currently underway at the school. The stories that follow highlight the work of five Hopkins nursing researchers who are doing their part to close the gap.

^top

Toward Cultural Partnerships with Staying Power

Miyong Kim, PhD, RN, FAAN subscribes to an approach that gives Johns Hopkins research initiatives a unique power.

“Traditionally, community health research has been ‘helicopter’ research. You come in, get the data, and get out,” she says. “Community people never see the result nor any benefit. Now we try to build partnerships—and structures that are sustainable.”

Kim is director of the Korean American Health Research Initiative, a community-based participatory research (CBPR) program within the Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing. The aim of such CBPR programs: to look carefully at the needs of different communities, help them build systems and train people to assist, and then help them get resources they need. Community-based participatory research promotes “co-learning,” in which both sides learn from one another, and emphasizes “community driven” efforts.

“It is carried out with and by local people rather than ‘on’ them,” says Kim.

In Baltimore’s fast-growing Korean American community (it is now the city’s second largest immigrant population), Kim and her team have found that the incidence of disease such as hypertension, diabetes, and breast cancer is growing dramatically. In her recent study of Korean Americans in Baltimore, 32 percent had high blood pressure—much higher than the 24 percent rate among Americans generally and 22 percent among their counterparts in Korea.

Team member Gina Pistulka, RN, MSN, MPH found a similarly high incidence of diabetes—about 20 percent among the Korean American elderly she studied, compared to about 12 percent among European Americans. And among Korean American women over age 40, assistant professor Hae-Ra Han, PhD, RN found that less than half had reported having a mammogram, a rate much lower than the national average of around 70 percent. The finding is ominous, Han notes, because breast cancer “is rapidly increasing among Korean American women because of changes in diet and physical activity.”

Through their research, the scientists are exploring causes for such disparities. Kim has found that many in the Korean American community own small businesses that can’t afford to offer health care. Even if business owners have health insurance, they work such long hours that their time for visits to the doctor is extremely limited. There are other cultural nuances at work as well-such as language barriers, an unwillingness to advocate for oneself, and embarrassment over needing particular medical tests, she says.

In her mammogram study, Han found that some male Korean doctors are so constrained by social mores and privacy that they may not discuss topics such as breast or ovarian cancer. In one case, even after detecting a lump in woman’s breast, Han says, a doctor did not encourage the woman to be tested further. In the case of diabetes, Pistulka has found there may be a genetic distinction at play, one that prompts Korean Americans to store energy more readily. Or, their physiology may be affected by stress related to immigration, finances, and a new lifestyle.

Han’s solution was to build a network of volunteer community-based health workers to educate and encourage Korean American women about the cancer threat they face, take preventive action, and seek treatment. She has trained 15 volunteer community health workers and through them some 50 women—about half the goal—have to date made appointments for mammograms.

Pistulka and other researchers working with her found it easiest to encourage a change in behavior through culturally-based resources, particularly the church, which is the center of social life in Korean American culture in this country. “Few studies have tried to understand the perspective of Korean Americans. Without greater understanding of their unique position, health providers cannot offer care that meets their needs,” she says.

Kim is optimistic about the impact their research will have. “The system is so fragmented and hard to navigate for anyone, but especially a person with a disadvantage from the start,” she says. “I think that we can be a cultural broker and help them build health service structures that last.”

^top

Stressful Surroundings May Be Hazardous to Your Health

While Kim, Pistulka, and Han turn to the community for solutions to the health care problems of Korean Americans, Sarah Szanton, RN, MSN, CRNP is finding that the community can actually be at the root of health care problems for elderly people who live in impoverished areas. Many experience a destructive form of stress that grows from a loss of control, minimal social support, and surroundings that may be dangerous and difficult to navigate, Szanton says.

“There are people who have their children sleep in bathtubs out of fear that any place else is not bulletproof. To live with the fear that one’s grandchild might be shot has an effect physiologically,” she says.

Szanton, a doctoral student and John A. Hartford Foundation Building Academic Geriatric Nursing Capability Scholar, is conducting a two-year study that is examining links between cardiovascular disease and the stress of an impoverished lifestyle among women from 70-79. Specifically, she is examining “allostatic load,” what she describes as “the stamp” of a lifetime of stress. “It is measured,” she explains, “through the immune, cardio-vascular, and endocrine systems.”

In her study of 734 women who live in an impoverished Baltimore neighborhood, she has found that about 50 percent of heart disease in her study is not explained by individual risk factors such as smoking or high cholesterol. “One hypothesis,” she says, “is that other factors are the reasons for the unexplained risk. From what we know about the physiology of the stress response, these kinds of factors we would think would affect their blood pressure, their blood glucose, and their immune system, among other things,” she says.

The “observational” study is still underway and is intended to gather information about whether there may be a link between the higher levels of stress these women face and heart disease. Szanton says that despite a decade of work on women’s cardiovascular health, little work has been done to examine the impact of their surroundings.

She herself became interested in the issue of health disparities in older adults when she was a nurse practitioner and was making house calls to homebound patients in West Baltimore. She noticed that her elderly patients were nervous about going outside in neighborhoods that were unsafe, were anxious about the lack of cleanliness of their homes or the inability to get services they need, were worried about loved ones who were physically or mentally ill, and were concerned about security while they were in their homes. “It seemed to me the stressful environment might have an impact on their health,” she recalls.

Intent on finding out more, she received a two-year training grant from the Center on Health Disparities Research (with Jerilyn Allen ScD, RN, FAAN as principal investigator), which allowed her to launch her current study, funded by the NIH and the Hartford Foundation.

Though her study isn’t looking specifically at how to alleviate stress among the impoverished elderly, Szanton has some thoughts about what might help. Providing universal health care could reduce some of this stress and in turn, reduce illness, she says. And she supports efforts to keep older citizens actively engaged, such as a program called Experience Corps, which has elderly people work 15 hours a week in local schools.

“When there is positive stimulation for older adults, there are big health benefits. The schools benefit. And they are a major resource. If we can make this resource useful, it is a win, win, win situation,” she says.

^top

Straight Talk About STDs

In her area of health disparity research, Hayley Mark, PhD, MPH, RN has found a need for some clear talk about sexually transmitted diseases—particularly among minority communities. In 2004, gonorrhea rates were 19 times greater in African Americans than in whites, four times greater in American Indian and Alaska Natives, and twice as great among Hispanics, Mark notes.

While the causes of the disparities are admittedly complex, Mark says there are a few “givens.” Education and treatment are often not readily available to these groups. What’s more, she says, “the presence of a small number of individuals who change partners frequently has dramatic implications for disease trans-mission and persistence of a curable STD in a population. These individuals are considered the core in STD transmission.”

Mark’s interest in STDs began during graduate school when she was counseling students about protecting themselves from these embarrassing, under-reported, and often misunderstood diseases. “I was struck by the fact that students had a lot of good questions, but would ask them only when I made it clear that I was not there to judge them.” She saw the same thing as an RN at a public health clinic, where pregnant women often wanted good information about these diseases, but only would seek it when they were assured they were getting “accurate information without judgment.”

She has done extensive research and advocacy in the area of STD prevention, and now has launched a study to measure the emotional toll that a positive test for herpes takes. Some 98 students were willing to participate and be tested for herpes. They reported on their knowledge, depression, anxiety and sexual behavior before and after testing. The results of the study, she believes, could help clinical workers offer more effective counseling and follow-up to teens once they are positively diagnosed.

Mark has completed another study with girls ages 14 to 16 that is designed to educate them about the increased health risks of douching – a procedure that boosts the risk of many vaginal infections including bacterial vaginosis, pelvic inflammatory disease, and other sexually transmitted infections. To make the education process more effective, she is also working with their mothers or other women who influence them.

Straight talk, Mark has found, is most effective. “People from all economic groups are reluctant to seek care for STD symptoms or seek accurate information,” Mark says. For the disadvantaged, there are additional barriers that are particularly burdensome, such as lack of access to service.

“People need to be able to access treatment and preventive methods and they need access to information. We have to reduce the stigma, and start talking and educating people in a way that talks about these things as diseases, not as a moral statement.”