Hopkins nurse leaves legacy of desegregation

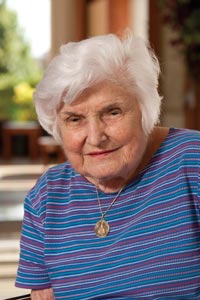

One of Louise Cavagnaro’s “major, largely unsung achievements as an administrator was the desegregation of the Johns Hopkins Hospital, ward by ward,” says Nancy McCall, an archivist at the Alan Mason Chesney Medical Archives of the Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions. “She also earned the trust, support, and affection of black employees, especially in the facilities and housekeeping divisions. There are many still working who remember her.”Louise “Cavi” Cavagnaro, an honorary member of the Johns Hopkins Nurses’ Alumni Association, received her first nursing degree in 1943 and served as an Army nurse in World War II. In 1953, she started working at The Johns Hopkins Hospital, where she held numerous administrative positions before retiring in 1985 as assistant vice president. It was then, at the age of 65, that she began volunteering at the Alan Mason Chesney Medical Archives. This December, she retired after 25 years of volunteer service.

Cavagnaro, a former Army nurse, Hopkins administrator, and longtime friend of Johns Hopkins Nursing, was largely responsible for the hospitals desegregation in the 1950s. Following are excerpts from her 1992 essay on the topic, which is online atwww.nursing.jhu.edu/history.

Excerpts from “A History of Segregation and Desegregation at the Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions”

by Louise Cavagnaro, 1992

Johns Hopkins, a Quaker, came from a family who freed their slaves before the Civil War and the 14th Amendment of the constitution was enacted. In his letter to his Trustees he said that the Hospital “shall admit the indigent poor—without regard to sex, age, or color…”

Nurses serve patient meals in segregated gynecological ward at the Johns Hopkins Hospital Women’s Clinic, 1939.

The second patient admitted to the Hospital in 1889 was “colored” and became the first of many to be admitted to the Hospital. At the end of the first full year of operation, 13.6% of the patients were listed as “colored.” By 1900 this percentage increased to 20.7%…All Hospital patients were to be treated with respect. The earliest House Staff manual (about 1950-51) notes the policy of the Hospital to be that adult patients would be addressed as “Mr., Mrs., or Miss, or by their special title such as Dr. or Rev…” A first name was to be used only where the patient indicated that he/she be so addressed.

Despite this policy, [a member of the medical faculty] told me of an incident that occurred in 1947 when he arrived from Harvard Medical School to be an intern on the Osler Medical Service. When he referred to one of his black female patients on Osler 3 as “Mrs. —,” he was told by his assistant resident that “I made the patient uncomfortable calling her “Mrs. —,” and that it was better to call “colored” people by their first names…”

As I joined the Hospital Administrative staff in 1953, I was an active participant in the program to eliminate “separate facilities” for “colored” and “white.” Actually the separate facilities were for Americans of African descent. Asians were never segregated…

Desegregation of inpatient facilities began in the 1950s. Marburg, which was private medicine and surgery, was the first area to be involved. There were no general announcements or proclamations… In 1959 full integration of the ward services in Surgery was approved by Dr. Alfred Blalock… The last inpatient service to be desegregated was in the Psychiatry Department… The change occurred sometime between 1968 and 1973.

Segregation: It’s History

Public Facilities

- Segregated facilities included dining facilities, locker rooms, [drinking fountains], and bathrooms.

- Ms. Edith Rieder, a nurse anesthetist who arrived in 1946, remembers the “colored” and “white” waiting rooms outside of the General Operating rooms on the bridge connecting the Carnegie Building with the Halsted Building.

- Some clinics had “colored” and “white” days, but the Accident Room was never segregated nor was the Emergency Room which took its place.

- The entrances to the Hospital were never segregated nor were the outpatient facilities.

Patient Care

- The December 9, 1890, Trustee Minutes “noted the need of a separate ward for colored people…”

- The “colored ward” opened in March 1894 with men on the first floor and females on the second floor.

- [In 1916], two cement refrigerated rooms [morgues] were constructed, in the Pathology building, one for white patients and one for “colored patients” … these separate facilities were retained as such until 1960.

- [A member of the medical faculty] remembers that when he arrived in 1947 the shelves were labeled “white blood” and “colored blood” and that all of the blood bottles were labeled as either “colored” or “white.”