By Mat Edelson

Illustrations by David Fullarton

Baby boomer nurses are moving toward retirement and seeking to share their knowledge with today’s young, tech-savvy nursing students and recent graduates–the late-arriving Gen Xers and so-called ‘Millennials.’ But bridging this “generation lap” will require some serious educational reengineering.

It’s 2:46 in the afternoon, and on the 8th floor of the Outpatient Center, Mr. Collins’ day is about to get a whole lot worse. “I can’t breathe,” he rasps to an anxious young nurse standing over his bed. “My chest hurts!” Within seconds his condition deteriorates, not because of his medical situation, but rather his programmer. In the next room, unseen by the students flooding into Mr. Collins’ room, is nurse educator Susan Sartorius-Mergenthaler, RN. With a flick of the wrist and a few taps of her index finger, she’s sent Mr. Collins’ vital signs into a crash.

It’s 2:46 in the afternoon, and on the 8th floor of the Outpatient Center, Mr. Collins’ day is about to get a whole lot worse. “I can’t breathe,” he rasps to an anxious young nurse standing over his bed. “My chest hurts!” Within seconds his condition deteriorates, not because of his medical situation, but rather his programmer. In the next room, unseen by the students flooding into Mr. Collins’ room, is nurse educator Susan Sartorius-Mergenthaler, RN. With a flick of the wrist and a few taps of her index finger, she’s sent Mr. Collins’ vital signs into a crash.

Whether Mr. Collins will burn is now in the students’ hands. As they flock around the life-like dummy, this is their moment of truth, of finding out whether they can recall in a crisis what was learned at leisure. It is not a time for argument, but action, when immediately accepting the responsibility for a role could be the difference that brings Mr. Collins back from the dead.

With the monitor over his head now showing Mr. Collins is in full arrest, Sartorius-Mergenthaler, on the blind side of one-way glass, watches as the students, on their own, galvanize into a functional team. “Good, good,” she murmurs, as one student climbs a tiny footstool and begins chest compressions, coordinating her movements with another on an oxygen bag. In a corner of the room, a third scribes each action, checking off each step to prevent errors as the needles fly, the drugs are shot into IV tubes, and the defib unit at the foot of the bed is brought up to full charge.

“I need a little goop!” pleads one nurse, calling for the conductant as she slaps on the pads that will send some 200 joules of electricity surging into Mr. Collins body. Within three minutes the room hits full crescendo, and the one word that every new nurse is familiar with fills the room.

“Clear!” yells a student, and, somewhat amazingly, everyone remembers to do just that as she hits the red detonator button on the defib.

It’s not enough. Sartorius-Mergenthaler, a baby-boomer who never had an opportunity to learn through simulations when she was in nursing school, wants these first-year nurses to think through this emergency. Manipulating the computer program, she makes sure the charge doesn’t put Mr. Collins’ electronic heart back into sinus rhythm. But there’s no panic in the room, just a quick regrouping, another “Clear!”, another surge…and a momentary wait that seems to go on forever as the defib unit ‘analyzes’ the shock. A few agonizing seconds later, the digital voice announces the result.

“No additional shocks needed,” it says. Smiles light the room as five bodies that are definitely not dummies suddenly remember to breathe. It’s 2:51. Mr. Collins is alive, and if not exactly healthy, certainly no longer in crisis. The young nurses present have learned their lessons well.

Then again, their teachers are finally speaking a language they truly understand.

The Generation Lap

Back in the hippied ’60s, speaking truth to power was summed up with the catch phrase “Never trust anyone over 30.” Now that same boomer generation is scrambling to figure out how to teach anyone under 30. In what some former flower children turned faculty consider karmic irony, those who as a generation loudly questioned authority suddenly find themselves on the receiving end of an educational upheaval unlike anything they’ve faced during their careers. It’s being driven by their offspring–late-arriving Gen Xers and so-called ‘Millennials’–young, tech-savvy nursing students and recent graduates whose upbringing, expectations, and uninhibited expression of thought are markedly different than previous generations.

Conversations with more than 20 senior nursing faculty from the School of Nursing, The Johns Hopkins Hospital (JHH), and the Institute for Johns Hopkins Nursing (the school’s continuing education arm), as well as interviews with recent grads and current traditional and accelerated program students, reveal the depths of the generational divide.

Conversations with more than 20 senior nursing faculty from the School of Nursing, The Johns Hopkins Hospital (JHH), and the Institute for Johns Hopkins Nursing (the school’s continuing education arm), as well as interviews with recent grads and current traditional and accelerated program students, reveal the depths of the generational divide.

The gulf is one of both style and substance, which can only be exacerbated–or healed–by educational choices in approach and access. On one side are the emerging students. They seek the teacher-as-mentor, an educator capable of adapting complex learning material to the individual’s preferred learning style, delivering curricula in the high-tech, high-engagement manner that’s defined their lives.

“I’m on the cusp of Gen X and Gen Y,” says 29-year-old Meghan Greeley, who graduated with the accelerated class of 2008 and is pursuing a master’s in nursing and public health. “We’re reactionary. With technology, it’s enabled us to do so much that expectations have changed. We want to know right now.” (See “Just-in-time” learning sidebar)

On the other side are these very educators, so used to being the gatekeepers of information, suddenly realizing that the walls to which those gates are attached are quickly being scaled and circumvented. The information-dense, classroom-accessible Internet is turning education from a monologue into a conversation, and teachers are questioning their past classroom methods.

“I’ve won ‘teacher of the year’ several times,” Lori Edwards, MPH, APRN, BC, a veteran educator who teaches Public Health Nursing and elective courses in the school. “But there’s a disconnect now. It’s hard to know what the right teaching strategies are,” says Edwards. “I’ve wondered ‘am I good at this anymore?’ I hope and believe that I am, and I’m very committed to figuring this out.”

Edwards is in the majority. For all the occasional frustration expressed by a vocal minority of students, there’s a belief among faculty that harnessing the next generation’s energy and assets can produce a phenomenal pool of visionary leaders who embrace new ideas far more quickly than the current status quo.

“Younger students are into multi-tasking. We have all these student activities here. The Millennials will sign up for every extracurricular activity they can,” says assistant professor Betty Jordan, DNSc, RNC, co-director of the school’s Birth Companions Program. “They’re very positive. They’re aware of community service; they’ve participated in it from grade school. They really want to change nursing, based on evidence. And they’re not real tolerant when we say, ‘well, this is evidence but we’re not quite there yet in practice.’ They’re challenging us, saying ‘Why not? Why not?”

According to Diana G. Oblinger, PhD, a former Executive Director for Higher Education at Microsoft whose lectures include “Educating the Net Generation,” Millennials are noted for being, in her words, “digital, connected, experiential, immediate, and social.” Leah Yoder, MSN, RN, who gives talks on generational differences to SON faculty, says this often frenetic framework centers on one constant truth.

“This is a generation of natural problem solvers,” says Yoder. “They buy a game, stick it in whichever box, and begin to play without even reading the instructions. It’s called ‘Failing Forward.’ If something doesn’t work when they’re playing, they start over, make different choices, and start over again. That’s how they look at life.”

Generational differences are nothing new–every teenager thinks they’re more knowledgeable than their parents–but most researchers and educators agree that the Millennials are the first generation that can back up that claim. Weaned in a world of home computers, Google, and video games, their education and socialization has been tech-dominated, to the point that researchers hypothesize that their brains synoptically differ from their parents, possibly affecting everything from learning styles to coping skills.

Instead of a generation gap, the term ‘Generation Lap’ was coined to convey the impatience many students express to teachers who can’t keep up with–let alone understand–the devices and applications that young learners depend upon to empower those blazing mental download speeds.

And Millennials consider voicing their knowledge and opinions to be practically a birthright.

“We were ‘told’ that we should give positive reinforcement to our children. So their opinion has been doted on and encouraged by parents. And they’re used to being told ‘You’re smart, you’re great, you’re fabulous,” says Diane Aschenbrenner, Course Coordinator for Principles and Applications of Nursing Interventions. “As a result, they’re very challenging in the classroom and they feel that, whatever their opinion, they have a right to express it. They don’t use the chain of command, nor defer to experience. It’s very egalitarian to them.”

“In the U.S., you see yourself much more as a peer with your teacher,” notes 28 year-old Abby Crisman, a graduate of the accelerated class of 2009, who studied for several years in India, where faculty are still revered. Today, she is enrolled in Hopkins’ MSN/MPH program. “Now, I think many students approach it as it’s the professor’s job to earn their respect. The professors don’t necessarily start out with it.”

“In the U.S., you see yourself much more as a peer with your teacher,” notes 28 year-old Abby Crisman, a graduate of the accelerated class of 2009, who studied for several years in India, where faculty are still revered. Today, she is enrolled in Hopkins’ MSN/MPH program. “Now, I think many students approach it as it’s the professor’s job to earn their respect. The professors don’t necessarily start out with it.”

So why are these unruly students being coddled in what’s supposed to be a professional school setting? One reason is competition for qualified candidates. Between the recession and the high cost of education, academia is being dragged into battling for tuition dollars. The result? The student as a silent, grateful sponge is being replaced by the demanding student-as-consumer, who, like a car buyer, expects a ton of whiz-bang standard features to go with that degree before ponying up the cash.

“I am paying a lot of money to go to school here, so I want an email response from teachers in 24 hours. I’ve asked them for that. Faculty have a high expectation of us, and students have a high expectation of faculty. If faculty expect a response from us within a certain time frame, the students expect the same courtesy. That’s a consumer approach, but I’m paying for this education and I expect certain things,” says 21-year-old Allyson Dibert, a senior in the traditional class of 2010.

Dibert isn’t alone in her feeling that money talks. Numerous young nursing students and recent graduates interviewed recite a similar quid pro quo refrain, and, for a change, administrators seem to agree, giving consumer complaints (i.e., student evaluations) unprecedented weight.

“I’m encouraging faculty to use midterm evaluations to ask students how things are going and are there changes we should make,” notes Anne Belcher, PhD, RN, AOCN, CNE, FAAN, Director of the Office of Teaching Excellence, an initiative set up in 2008 to bring new technologies and multiple learning styles into the classroom and clinical sites, and to measure their value to students and faculty. “We might not make all of the suggested changes, but we acknowledge there’s always room for improvement.”

Students aren’t the only ones applying pressure to upgrade curricula. Hospitals–and Johns Hopkins is no exception–have long complained that nursing schools simply aren’t doing their job. One study found 97 percent of nursing school administrators claimed their graduates were well prepared to enter the workforce, yet only 11 percent of hospital administrators agreed. They especially cited huge retention issues as shell-shocked grads often fled their jobs within a year, taken aback by the grueling, tech-intense nature of the work.

“We’re still doing clinical education like I was taught 30 years ago. That needs to change,” says Dean for Academic Affairs Pam Jeffries, DNS, RN, FAAN, ANEF, an innovative educator hired from Indiana University to infuse technology into the classroom.

But where to begin?  The ‘wish-list’ of the next generation of students and future employers is long, complicated, expensive, and resource-intense. More flexible schedules. Online Courses. 24/7 email access to faculty. Simulation labs. Podcasts. One-on-one clinical mentoring. Chat rooms. DVDs. Discussion groups. Interactive classes. Teaching to multiple learning styles.

The ‘wish-list’ of the next generation of students and future employers is long, complicated, expensive, and resource-intense. More flexible schedules. Online Courses. 24/7 email access to faculty. Simulation labs. Podcasts. One-on-one clinical mentoring. Chat rooms. DVDs. Discussion groups. Interactive classes. Teaching to multiple learning styles.

Boring lectures? Blasphemy. Staid textbooks? That is so 20th Century. “Here we are now, Entertain us!” sang Nirvana, foreshadowing the next generation’s expectation of their educational experience.

Unrealistic? Perhaps. But the future of nursing may depend upon how well Hopkins and other nursing schools make the unrealistic real and viable.

“Sage on the Stage” or “Guide on the Side”?

On Nelson 8, Nicole Canepa, 23 years old and a member of the traditional class of 2011, is one of the lucky ones. The California native was among a dozen Hopkins nursing students randomly chosen for a pilot program known as CAPP–the Clinical Academic Practice Partnership (see sidebar). While the rest of her classmates are going through ‘traditional’ clinical education–i.e., one faculty mentor on the floor teaching upwards of eight students–Canepa is receiving personal tutelage from preceptor Karen Blymire, RN, BSN, ONC.

Actually, this “new school” concept is about as “old school” as it gets, harkening back to the apprentice/journeyman model of medieval times.

Her blue eyes wide with a combination of excitement, awe, and stage fright, Canepa is shadowing Blymire’s every move. For Blymire is not only Canepa’s preceptor, but also a busy nurse juggling a normal caseload. On this day, that includes a woman recovering from spine surgery, a man who tore up his knee playing football, and an elderly diabetic. Clutching an orange injection pen that resembles one of Canepa’s overused highlighters, Blymire leads her charge into the diabetic’s room, where she dispenses a quick trick-of-the-trade.

“Hold it against her arm for 10 seconds,” says Blymire, placing the injector against the woman’s fleshy right tricep as Canepa looks on. An audible ‘click’ sounds as Blymire depresses the head of the injector. “Count it out…2 seconds…3…4…5…that way there’s no leakage.”

Over the next 8 weeks, Canepa and Blymire will go from spending four hours once a week on the floor to a full 12-hour shift during the course’s final session. CAPP is exactly the kind of educational experience Canepa was looking for when she came to Hopkins.

“Sitting in a classroom, you can only learn so much. You learn so much more in a setting like the hospital. I get to look at nursing through Karen’s eyes a bit and see what goes on during her shift. I want to work in a hospital, so why sugarcoat it now? I’m stoked to see what you do from start to finish on a shift.”

CAPP is part of a greater educational experiment taking place in both the School of Nursing and the various Hopkins clinical facilities. The challenges educating Millennials are fairly obvious, but the solutions? They’re not nearly as clear. Precious little data has been collected as to what teaching strategies are most effective, and yet the world of 21st century nursing is taking shape. Between telemetry, technology, testing, ever-changing protocols and the mounting use of computerized bells and whistles, new nurses will need access to more information than they possibly can memorize.

In its 53-page final report last year, the Office for Teaching Excellence Task Force defined numerous recommendations in instruction, leadership, and organizational development squarely aimed at strategies addressing students’ preferred learning styles. This includes orienting staff and students to generational differences from the moment they arrive on campus.

But while the report goes out of its way to note that the student body is clearly multi-generational, including baby boomers embarking on second careers, much of the energy coming out of the school’s administration is focused on high-tech oriented, individualized applications more familiar to the growing number of incoming Gen Xers and Millennials.

On a programming level, that sense of personal interaction with both teachers and patients acting as mentors is noticeable across a wide range of initiatives. “Our teaching model will go from ‘the Sage on the Stage’ to ‘the Guide on the Side,'” says Leah Yoder, who runs SPRING, an orientation program for new grads at the Hopkins Hospital. “We have to be interactive, where the teacher is no longer going to be a talking head. In our model, the students or nurse grads will often look up the information in teams to solve the problems they’re working on that day, and the teacher will be walking around facilitating.”

The SPRING program, which stands for Social and Professional Reality Integration for Nurse Graduates, is a yearlong program for new nurses that provides a peer community and a formal forum for passing on the knowledge and experience of boomer and traditional generation nurses. A similar concept, the RN Nurse Fellowship Program, runs out of Howard County General Hospital under the direction of Vera Tolkacevic, MBA, RN.

As SPRING’s name suggests, a large portion of their curriculum, which consists of full days of training interspersed at three-month intervals throughout a new grad’s first year, deals with psycho-social issues. This includes courses in assertiveness training for better managing workplace stress. There’s a sense among educators that Millennials spent so much time in their daily lives socially interacting online that they need training to overcome an empathy gap that could negatively affect patient outcomes.

“One of our concerns teaching nursing is that you have to know how to communicate face-to-face and be aware of body language, things that you miss when you do social networking via technology,” says Yoder. “We’ve noticed in our interns that they sometimes don’t have those soft skills in communication and negotiation.”

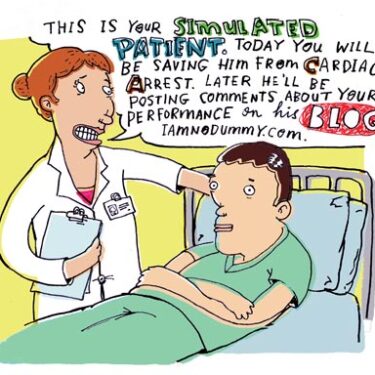

Not surprisingly, given the Millennials’ bent and the general direction of nursing, technology in a myriad of forms is involved in nearly every new teaching effort. Real-time simulations involving both manikins and computer monitors (known as ‘micro-sim’) have proven incredibly popular for teaching both skills and teamwork. Already used in the SPRING program at Hopkins Hospital (featuring the aforementioned “Mr. Collins”), the school’s Sim program was so well-received that it’s currently undergoing a renovation. When finished, it will contain two state-of-the-art simulation/mock hospital rooms, two debriefing centers, and a central control room for running simulations using human patient-simulator manikins.

“We’re going to videotape students during simulations so they can review them,” says instructor Diane Aschenbrenner, MS, APRN, BC, RN. “That way, it offers them the experience that we can show them steps they’ve missed, even when they say at first ‘Oh, I didn’t do that!’ For example, I can point out ‘here’s where you touched what was supposed to be a sterile field with your sleeve.'”

Simulations also allow students to delve into the very same software they’ll use at the bedside professionally. Research nurse Laura Taylor, PhD, RN, created simulations across all clinical classes that incorporate the same Eclipsys Point of Care electronic patient records software purchased by Hopkins Hospital. Now, students can take a mock history from a faculty member representing an 85-year-old patient with congestive heart failure, then attach their stethoscopes to a simulation manikin programmed to reproduce impaired breathing sounds.

“Then the students must integrate documentation on the Eclypsis electronic health record as part of their workflow. That’s what nurses do,” says Taylor. “Nurses can’t go home, have a slice of pizza and document their patient care while watching ‘House.’ The students have to document their work before they leave clinical and it is reviewed by clinical faculty.”

Theoretically, technology can reach students regardless of their particular learning styles. Kinesthetic learners–those attracted to the hands-on approach–are drawn to simulations. “The stumps are a great learning tool,” says student Allyson Dibert, “because a book would only say ‘wheezing goes with asthma,’ and you can’t really describe a breath sound.”

Meanwhile, visually-oriented learners want lectures supported with films, DVDs, anything that moves on the screen. For assistant professor Jodi Shaefer, PhD, RN, that meant a cameo from her daughter/actress, who she filmed in New York rapping mom’s introduction to her Nursing Research class. Says Shaefer, “I could have just stood up and read my syllabus. But do they listen to you when you do it straight? They loved it! It had them rolling in the aisles. And frankly, it was more fun for me.”

Meanwhile, visually-oriented learners want lectures supported with films, DVDs, anything that moves on the screen. For assistant professor Jodi Shaefer, PhD, RN, that meant a cameo from her daughter/actress, who she filmed in New York rapping mom’s introduction to her Nursing Research class. Says Shaefer, “I could have just stood up and read my syllabus. But do they listen to you when you do it straight? They loved it! It had them rolling in the aisles. And frankly, it was more fun for me.”

To help support this sea change in the curriculum, the school brought on Michael Vaughn as Assistant Dean for Information Technology and Integration, and hired two full-time experts in instructional technology–Theron Feist and Emily Jones–to aid faculty in moving technology into the classroom (see sidebar).

Administrators are also looking at the online course experience of the Institute of Johns Hopkins Nursing (IJHN) to see how continuing education models can be adapted to undergraduate and graduate education. Specifically, they’re focused on IJHN’s Guided Care program, a six-week web-based course that includes computer simulations and live ‘webinars’ (web-based seminars).

Given that other Hopkins schools such as the Bloomberg School of Public Health already offer online courses as part of their master’s programs, the nursing school is hoping to make a similar leap. On a practical level, increasing online course exposure allows students additional time to review materials and increases educational opportunities for those whose work or life schedules are too busy to come to campus several days a week. It’s also part of an effort, at both IJHN and the SON, to integrate what used to be separate parts of a student’s academic life into a cohesive whole.

On the IJHN side, Executive Director and long-time clinical nurse manager Jane Shivnan, MScN, RN, AOCN, says “For me, the needs of Gen Xers and Millennials are definitely a pressure for how we present ourselves to the world as well as how we design education. We now have the ability with new courses to have online discussion forums. I want to build a true community with more social networking for learners with a common interest.”

What this all amounts to is one great educational shakeout.

The Millennials have presented boomers with a challenge many thought they’d never face in their educational careers; the sudden, startling discovery that business-as-usual was no longer effective or desired. In their penultimate teaching years, the message is as clear as evolution: Adapt or risk becoming obsolete.

For some, the change will be too great, the need for constant student access too intrusive, the attempt to turn the classroom into entertaining theater too exhausting to attempt. But for those like Leah Yoder, this is a time of great opportunity. She and her ilk see themselves as being on the forefront of the new classroom, an interactive wonderland without walls or limits.

“We can be stubborn and teach the way we’ve always taught,” says Yoder, “but I challenge them to step out of the box. As a generation we hold a tremendous amount of expertise that needs to be passed on to this new generation. We can make this tremendous contribution to nursing by changing the way we teach and train.”

And ensure that the lessons of the past are not lost on those who will benefit from them the most.

Just in Time

An onslaught of new ideas and data is changing the way nurses learn.

For years, nursing schools held onto the notion that they could teach their graduates everything they needed to know about nursing. These days, they admit that’s just not possible.

“Years ago, there was a manageable amount of information to be taught, and an expert could keep on top of what was current in their field. Not anymore,” says Debra Case, MS, RN, the assistant director for nursing education and clinical information systems at The Johns Hopkins Hospital.

“Years ago, there was a manageable amount of information to be taught, and an expert could keep on top of what was current in their field. Not anymore,” says Debra Case, MS, RN, the assistant director for nursing education and clinical information systems at The Johns Hopkins Hospital.

With bedside technology and protocols changing constantly, today’s gold standards of care are rendered irrelevant within a startlingly short period of time, says Case. “We can’t prep nurses ahead of time on what they need to know in a year or two or three because there’s so much information out there.”

The result has been a movement to “just-in-time” information–relying on quick nuggets of vital knowledge from vetted sources accessible instantly via computer.

On the hospital side, this has meant numerous computers on the nursing units, and moving all protocols and technical manuals onto one website (longer protocols are in the process of having short summary statements added). At the school, moving towards the Just-in-time model frees faculty to teach more conceptually, sort of a forest-versus-the-trees approach.

“I think we have to teach the big picture, to focus on large topics like shock and oxygenation,” says Pam Jeffries, DNS, RN, FAAN, ANEF, associate dean of academic affairs. “In medication administration I can’t teach about 150 different antibiotics, but I can teach about general drug classes, side effects, and the nursing implications of giving an antibiotic.”

For younger students, Just-in-time learning is an extension of how they’ve experienced the world, accessing everything from movie times to breaking news at the instant they need the information. Now, the bullet points of PowerPoint presentations are giving way to summary podcasts that, in a just a few minutes, allow students to zero in on what matters in places where they’re most amenable to the material.

“It’s just another way for me to learn,” says 28 year-old Abby Crisman, a graduate of the accelerated class of 2009 and current MSN/MPH student. “The teachers often address questions on tests, what you need to focus on, in a podcast. Also, so much time is normally lost commuting everyday that to be able to sit on the shuttle and put a podcast on your iPod is wonderful.”

It sounds like a world Sgt. Joe Friday–“Just the facts, Ma’am”–would appreciate.

Students Sound Off

“In the U.S., you see yourself in the classroom as a peer, even when you’re a student. I think students now approach it as though it’s the professor’s job to earn their respect. They don’t necessarily start out with it.”

–Abby Crisman, accelerated ’09, 28, Currently in Family Nurse Practitioner/MPH program. Crisman studied for four years in India.

“I want to understand the application. Otherwise it’s ‘that’s great, but is that going to help me in the real world?'”

“I want to understand the application. Otherwise it’s ‘that’s great, but is that going to help me in the real world?'”

–Ghiselaine Cedeno, 21, Traditional Class of 2011

“The textbooks I’ve had in nursing school have been phenomenal, especially the CDs that come with some of them. They provide test questions and little games to play, which I really enjoy, because it’s an interactive thing. So I’m doing a crossword puzzle or a matching game, and it sounds silly because it’s toddler-ish, but it’s really how I learn. If I have a matching card that has a drug on it and I have to pick an adverse effect on another card, then I’m going to learn it as opposed to reading something over and over in a dry paragraph.”

–Allyson Dibert, 21, Traditional Class of 2010

“This was the most draining thing for us, the generational gap, the differences and the clashes between the needs of the younger generation and those of us who’ve been out in the world awhile. We’d have different learning needs and different psyches.”

–Anonymous

–Theresa Medicus ’08, 29, now working at The Johns Hopkins Hospital

–Suzanna Sherer, 35, accelerated ’10 and Returned Peace Corps Scholar, on changes in the classroom between faculty and students since receiving her undergraduate degree in California in 2004.

A 21st Century Education

Pam Jeffries makes sure students are getting clinical mentorship, simulation technologies, and online learning worthy of the Hopkins name.

From Indonesia to Indiana, Pamela Jeffries, DNS, RN, has spent her nursing career pushing the forefronts of education.

“With this generation, you have to keep them engaged, interactive, with real-time, real-world interactions. Everything has to have a purpose,” says Jeffries, the school’s new associate dean of academic affairs.

Last December, she arrived in Baltimore with a wealth of experience incorporating technology into the educational experience. Good thing, because she’s now in charge of meeting the technological demands of the computer-savvy Millennials.

Last December, she arrived in Baltimore with a wealth of experience incorporating technology into the educational experience. Good thing, because she’s now in charge of meeting the technological demands of the computer-savvy Millennials.

Jeffries has already launched several important initiatives, all designed to close what she says is “a practice/academic education gap” that’s well noted in the literature. The Clinical Academic Practice Partnership (CAPP) could well change how the school’s baccalaureate students experience preceptorships.

“Traditional clinical education has been one teacher with eight students. We’re still doing clinical education like I was taught in the 70s, thirty years ago,” says Jeffries, who designed CAPP to drop that student-teacher ratio to 1:1. Students receive training from a nurse preceptor on an active unit, in either Bayview Medical Center or Nelson 8 at Hopkins. “Students are getting socialized to nursing quicker having one-on-one with a preceptor at this level.”

They’re also better prepared going into that environment, as Jeffries shifts the curriculum to take advantage of simulation technology. This allows students to practice with lifelike computerized hi-fidelity manikins, sensors that attach to a student’s stethoscope and produce a myriad of body sounds, and video programs that test knowledge and skills. Jeffries is working with Diane Aschenbrenner to expand the school’s Sim Center, which, when finished this fall, will include two simulation rooms, a control center for faculty, a debriefing area, and the ability to stream video to other classrooms.

“Say I’m going to teach a class on care of a thoracotomy. I can sit and just talk for thirty minutes,” says Jeffries. “Or, instead, I can pull four students and have them do a simulation on a manikin that I can feed in live to the classroom and immerse the class in taking care of a ‘patient’ and they have to provide chest tube care and pain management. So the whole classroom watches this streamed simulation live for fifteen minutes, and then we debrief the whole class on what went right and wrong.”

Jeffries is also creating classrooms without walls by expanding the use of online education. She’s secured two grants to put the Clinical Nurse Specialist and Health System Management programs online, efforts that mobilize learning to accommodate a student’s schedule.

“Our learners need this kind of versatility where you can get an education 24/7. I’ve taught online courses at the master’s, PhD, and undergrad levels. Where you see a lot of activity is on the evenings or weekends. If they have families, it’s after they put their kids to bed and they can work on classwork, or on weekends is when they catch up because they’re not working their 40 hour job then and these students do what they can to obtain their education.”

If Jeffries has her say, it’ll be a 21st Century education they’re getting.

Digital Muses

When Hopkins nursing faculty find themselves flummoxed by the digital divide, they turn to the team of Emily Jones and Theron Feist, who are quickly establishing themselves as the school’s gurus in educational technology. The duo, the first hires last year as part of the school’s revamp of the technology infrastructure and offerings, bring divergent yet complementary backgrounds to a task that is nothing short of monumental.

Jones, whose title is Instructional Designer, is the school’s one-stop shop for faculty seeking the best ways to incorporate technology into all aspects of teaching. A gifted digital storyteller, Jones sees her job as helping faculty choose both high and low-tech approaches for their classrooms. “I try to instill confidence that faculty can use technology with little or no problems. Sometimes I’ve just told them about creative ways for getting active engagement, like slipping in a discussion session in the middle of a lecture, or having them write questions for guest lectures, as a way of keeping students alert and engaged.”

Instructional Technology Manager Theron Feist has spent his career developing and managing software and IT networks to increase community outreach in places as diverse as Fairbanks, Alaska and New York City. Feist sees his role as “letting faculty and administrators know what the possibilities are for using technology,” and keeping current on “the things that are ‘hot’ with the younger generation. A lot of faculty here spend so much time on their specialty that it’s not reasonable to expect them to keep up with every aspect of technology.”

The team has hit the ground running. Jones spent the past summer integrating Blackboard software into every course at the school, which she believes offers excellent opportunities for creating effective online communication. Blackboard, with its built-in ‘discussion board,’ is a great place to keep students up to speed.

Feist’s focus has been putting together a long-term strategic technology plan and expanding the school’s IT network and classroom hardware. Notably, he’s retrofitting teaching space to create so-called ‘smart classrooms’ that he says “capture full courses on video using a system that’s called Media Site. We also capture guest speakers and interviews.” Feist says there are currently three smart classrooms in operation, and “as more courses and classes go online, we have to continue to step up what we do in retrofits to increase capacity.”

The duo has just become a power trio, as newly-minted Assistant Dean for Information Technology and Integration, Michael Vaughn, MS, came on board in early November. It’s the latest move in what Jones says is a technological revolution that will better prepare students for the nursing challenges they’ll face as professionals, as well as making life easier for both students and teachers while they’re here. She’s already getting positive feedback: The use of online office hours, where students communicate with teachers in real time through the use of instant messaging, is a real winner. “I did it when I taught. Students didn’t have to haul themselves out of their dorm rooms and across campus.”

Besides, everyone knows you take criticism better when you’re still in your socks and jammies.