Her sister Eugenia, a DNP, had opened three successful weight-loss clinics, as her own boss controlling her work-life balance, and was living the life. Matilda Decker, paying her dues through the nursing ranks, noticed. “That’s what I want: flexibility as a nurse practitioner, a mother, and a wife.” She unabashedly hopped on her sister’s white coattails, and began charting a course to a DNP—with more prodding from Jean Thorpe-Williams, a Hopkins DNP alumnus and clinical faculty at the Johns Hopkins School of Nursing. Then, she opened her own clinic, Eden Healthcare Services in Dover, DE.

Why Delaware? Eugenia moved there first, felt at home, and that was good enough for Decker.

“I give my sister credit for everything,” says Decker, who still commutes to Baltimore and JHSON once a week for her work as JHSON clinical faculty—teaching health assessment and synthesis practicum and serving as a simulation facilitator.

But it is her entrepreneurial endeavor that makes everything work, and Clinic No. 4 isn’t hurting for clients.

“There’s a great need for providers in Dover,” she says. Decker’s biggest community is military veterans, both retired and active duty, through a contract with Veterans Evaluation Services. The freedom she affords herself as a nurse practitioner means time to talk to the vets, to listen, to understand. “They are amazing patients. People don’t see what they go through, or hear their experiences.” Bonus: After all those years of drilling in the military, “There are so nice and polite.”

She also earned the credentials that allow her to do health assessments and clearance for long-haul truckers and others seeking a CDL, or commercial driver’s license.

All in all, it’s just right.

But what about her sister’s three clinics? Will Decker expand to match? You can bet she’s thought about it. This too: “You can get bigger, but bigger means more work, and then you’ve got a choice to make.”

She’s hoping to use leadership to build slowly and smartly, so that her own work-life balance is mimicked in any clinics she does eventually launch. “You need leadership to put systems in place to serve your communities, but also keep your own work-life balance and that of your employees too,” says Decker, who operates her lone clinic with just one assistant. “If the workers are fulfilled, then people are going to want to come to work. There’s always a right way to do it.”

Spoken like a Johns Hopkins DNP.

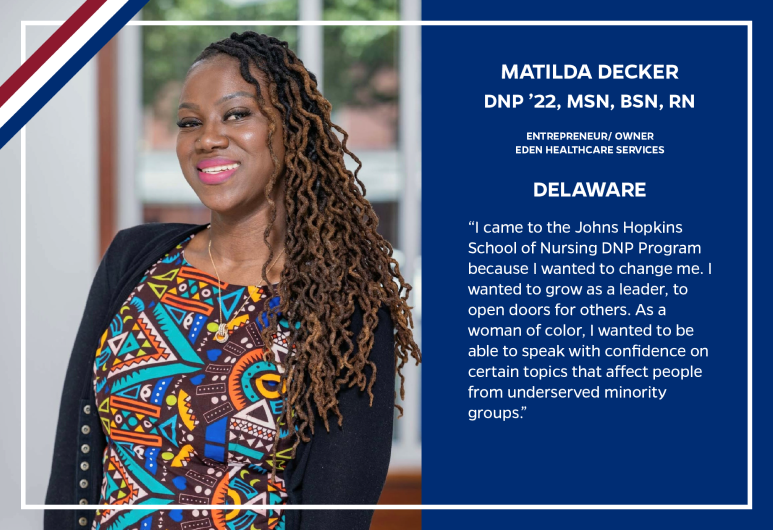

“I came to the Johns Hopkins School of Nursing DNP Program because I wanted to change me,” she explains. “I wanted to grow as a leader, to open doors for others. As a woman of color, I wanted to be able to speak with confidence on certain topics that affect people from underserved minority groups.”

She had role models already: JHSON faculty members Yvonne Commodore-Mensah and Diana Baptiste, increasingly looked toward as researchers, spokespersons, and advocates for underserved communities and prominent figures in Decker’s application essay for JHSON.

“I wrote in my essay that I wanted to work with them. And then it happened! If you laid my essay up against my DNP experience, that’s exactly how it turned out.”

Decker, originally from Ghana—would like to return some day to help address health inequities among underserved populations there.

“I am a woman of color, a nurse practitioner, a Ghanaian, an African woman who loves people,” she says. “I want to use nursing to build a better place in the world.”

Now if she can just persuade her sister to go first. — Steve St. Angelo

Click here to learn more about the programs at the Johns Hopkins School of Nursing.

Go to unitedstatesofnursing.org to see more stories in The United States of Nursing.